JORDAN’S FEAR OF THE ISIS

There are two countries that fear more than others the spread of the ISIS, their military conquests and their destabilizing effect: Lebanon and Jordan. This is due in part to the presence of extremists and terrorists on their territory. Lebanon is a country that has always coped with institutional instability and which is, at least in part, used to facing risky social, political and military circumstances and to finding solutions through internal mediation. Jordan, on the other hand, belongs to that part of the world that thrives from its belonging to a well-defined international context; a country that has its own, non-negotiable, internal and foreign policy; and which has a monarchy which, after the death of king Hussein, is in need of reaffirming its role and prestige. This exposes Amman to the risk that derives from the spreading Islamic extremism in the region, which the Jordanian monarchy is trying to oppose.

Collateral effects

The Syrian civil war, the rise of the ISIS and its spread throughout the Iraqi territories are elements which undermine the stability, if not the survival, of the Hashemite regime. The 179 Km border with Iraq and the 379 Km border with Syria are an ominous reminder of this. The first, tangible, side effect of this situation on Jordanian society is the presence of over 680.000 Syrian refugees in the country. The real figure is probably rounded down substantially, since it is based on the UN’s data. Analysts speak of over 1.5 million Syrians scattered across Jordan, to which one must add at least 1 million Iraqis and about 600.000 Egyptians. For a country that has a total population of roughly 7.5 millions, this incredible mass of refugees represents not only an economic burden, but a social threat as well. Especially since it is reasonable to assume that among these million visitors, some may actually be involved in Islamic terrorism.

It is therefore on the internal security level that the Jordanian reign runs the greater risk. There are presently over 2.000 Jordanian volunteers that fight among the ranks of the ISIS and of Jabhat al Nusra, both in Syria and in Iraq. Also, according to polls carried out by the University of Amman, a rough 10% of the population allegedly sympathizes with Islamic extremism. Demonstrations that took place in June 2014 in Ma’an, in the south of the country – a region which has been the theater of numerous uprisings and Salafite infiltration and where many volunteers have traveled to join Jabhat al Nusra – seem to confirm this statistic. Another hint is the recent discovery and arrest of about 30 alleged terrorists that were preparing and/or organizing terrorist attacks within the Jordanian realm.

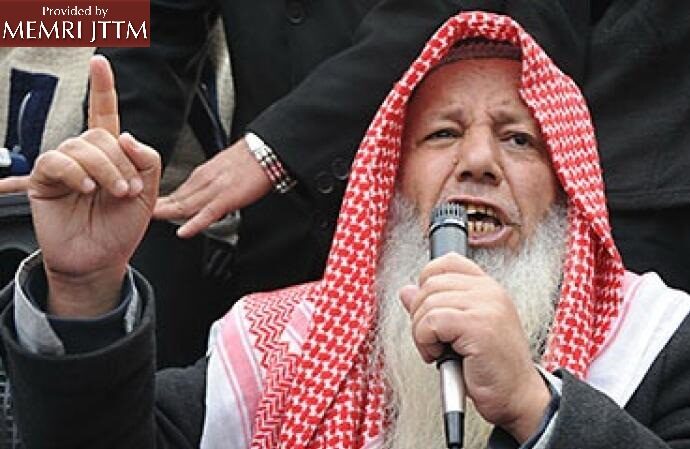

Abdul Majid Thuneibat

The Jordanian Muslim Brothers The potential support for extremism becomes even more worrisome if it is coupled with the activism and social rooting of the Muslim Brothers in Jordan. Politically speaking, the Brotherhood is the opposition, and operates within the bounds of a legal context with respect to the Islamic Action Front (IAF). In more real terms, the group is constantly fueling disorder and trying to ride the social resentment of the local population. Lately, the (re)banishing of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the shunning on the part of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries and the marginalization of Hamas have created much tension within the Jordanian branch of the Brotherhood and have widened the gap between those who wish to operate within set rules and those who would rather adopt radical initiatives. The internal clash within the Muslim Brothers found its apex on February 14, 2015, when the organization was split into two separate groups. The council of the Shura, the uppermost governing body of the Brotherhood, expelled 10 members of the organization whom, in turn, demanded and obtained the legalization of a new political party. In practice this new faction of the Muslim Brothers, headed by Abdul Majid Thuneibat – which is sometimes described as being a “reformist”, but who is actually just pro-government – wants to sever the ties with their Egyptian counterpart and with Hamas, a choice which is strongly criticized by the hawks within the movement. This confrontation sees the Council of the Shura, which approved the ousting of the dissidents, against the Council of the Students of the Muslim Brothers, which supports Thuneibat. The operation serves to draw a net distinction between the hawks, who want to continue supporting the claims and the uprisings of the Middle Eastern brothers, and the doves, who want to operate legally in the Jordanian context alone. The internal clash within the Jordanian Brotherhood has drawn Hamas in as well. The organization was instrumentally accused by Abdul Majid Thunebait of creating a secret branch within Jordan. The circumstance was, of course, denied by the leaders of Hamas, but has nonetheless threatened the long years of negotiations carried forth by Khaled Meshal, the head of Hamas’ political office, in his attempt to rekindle relationships with King Abdullah II; Hamas was banished from Jordan in 1999.

The risk of fragmentation

Accepting the request by Thuneibat to legalize its branch of the Muslim Brothers is aimed mostly at making the opposite faction, which is still numerically prevalent, illegal. The Jordanian government is acquiescent, or at least favorable, to the break-up which, initially, seems to weaken the Brotherhood. Yet they too fear the consequences of forcing a part of the movement into clandestine activity and the security issues that could derive from such a move. The Muslim Brothers in Jordan count on an active militia of 6 to 7 thousand men and could easily blend in with the militias of the Sheikh of the ISIS, Al Baghdadi. This is the reason why the Jordanian Brotherhood, despite the mounting pressure of the Gulf countries and of Egypt, was never included in Amman’s list of terrorist organizations. In order to launch his initiative, Abdul Majid Thuneibat emphasized the added value of his belonging to a Bedouin tribe which is juxtaposed to the majority of the Council of the Shura; the latter being more supportive of Palestinian claims, with all that this implies in the region. We shall not forget that, despite the fact that Palestinians account roughly for half of Jordan’s population, the Hashemite monarchy bases its force and consensus on the Bedouins. In order to see the full picture, we must add that the Islamic Action Front (IAF) is not currently represented in the Jordanian parliament – they boycotted the latest general elections – and they therefore act both politically and socially on the margins of legality.

The ties with terrorism

The relation between Islamic extremism and the internal situation of the Muslim Brothers constitutes, on the internal level, one of the main threats for the stability of Jordan’s monarchy. The leader of the IAF, Sheikh Hamza Mansour, has recently stated that the Caliphate can include Jordan, albeit with the consent of the population, and a similar view is shared by the Jordanian Salafites, headed by Mohammed Shalabi (aka Abu Sayyaf).

Recently, in order to lessen – on the religious level – the appeal of radical groups and to invalidate the brutality of the ISIS, the Jordanian authorities have released two theologians who are famous for their radical stance. The first, Abu Qatada, aka Omar Mahmoud Othman, is a Jordanian/Palestinian who was extradited to the UK in 2013 for terrorism and who has recently and, perhaps, not casually, been found not guilty. The second is Abu Mohammed al Maqdisi, aka Assem Mohammed Tahir al Barqawi, also a Jordanian/Palestinian, who was sentenced to 5 years in prison for recruiting mujaheddin in Afghanistan and who is well known to Jordanian prisons for having spent 16 years behind bars for his involvement in terrorism activities. His writings were a source of inspiration and legitimization for Abu Musab al Zarqawi in Iraq and for Ayman al Zawahiri in Afghanistan. The release of both extremists was part of a trade off where the two agreed to openly accuse the ISIS once outside.

Abu Mohammed al Maqdisi

Choosing a side Apart from the endogenous threats, there are those coming from outside as well. Jordan is firmly opposed to the ISIS; this is due in part to the international context in which the country operates – of which the USA, Western countries and, in part, Israel, are the guarantors – and in part by the social and political beliefs of Jordan’s monarchy. The country’s military effort was evident when one of its fighter planes was downed over Raqqa on December 24, 2014. The pilot of the Jordanian airplane was captured and burned alive on January 3, 2015. The circumstance strengthened the Jordanian anti-ISIS stance in terms of their military involvement – see the “Martyr Muath” aerial retaliation and the deployment of armored vehicles along the borders with Syria and Iraq. The recent conquest of the passage between Jordan and Syria by Jabath al Nusra has further increased the threat of instability. In the past few years, Jordan became first the center of the struggle against Bashar al Assad’s regime, then the heart of the struggle against the ISIS. Amman harbors about 8.000 US soldiers on its territory, especially ‘elite’ groups, an aerial unit in Mafraq, where the CIA trains Syrian rebels (the US administration has recently allocated half a billion dollars for the training of at least 5.000 rebels in the coming year), and an Operative Military Command in Amman where Americans, Saudis and members of other Gulf countries coordinate operations in the region. Jordan allows rebels to cross its border and to travel back to Syria with weapons and money, therefore supporting their military activity. The importance of Amman in the fight against the ISIS and against the Syrian regime was emphasized by the recent visit, on March 5, 2015, of the leader of Al Quds, the special units of the Revolutionary Guards: Iranian General Qasem Soleimani. The visit landed on the eve of operations to recapture Tikrit on the part of the Iraqi army with Teheran’s support. Soleimani met with the director of the GID (General Intelligence Directorate), General Faisal al Shoubaki; it is not clear whether the General met King Abdullah as well. The subject of the meeting was the presence of about 15.000 Shiite militiamen in Syria, a part of which are Iranian. The General was welcome with great enthusiasm, even in terms of protocol, which implies that, in the event of a rekindling of relationships between Iran and the Gulf countries, Jordan could play a central role – provided the Saudis agree to it. Amman has (re)started diplomatic exchanges with Teheran last September, with the designation of a new ambassador to Iran and, after Soleimani’s visit, with the visit in Teheran of the Jordanian foreign minister Nassir Judeh. The US Chief of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, travels often to Amman to speak with local authorities. The US have recently approved substantial military aid in favor of the Jordanian reign for the year 2016.

An imminent danger

Yet, as we mentioned, despite the military campaign and the international support, the Jordanian realm is not safe from imminent danger. Although some terrorist cells that were allegedly planning attacks in the country have been arrested, Jordan borders war zones, with the possibility of further terrorist infiltration, and there is a florid market for smuggled weapons. The Hashemite dynasty has always had a bumpy relationship with the Saudi monarchy due to the competition between the two for legitimization in the control of the holy sites, where each of the parties claims to be a descendant of the Prophet. Nowadays, instead, due in part to the common enemy, ISIS, Amman and Riyadh have gotten closer. This nearness produces for Jordan, a country without resources and that lives off international donations, new financing which is rather useful in relieving poverty and social upheaval in a country with an unemployment rate between 25 and 30 percent. Unlike his father Hussein, king Abdullah still has to consolidate his role of monarch in the eyes of the local population. The death of the pilot Muath al Kassabeh and the king’s participation in the funeral function have bettered the image of the king and especially that of his wife Rania, of Palestinian origin, who is often criticized for the lavishness which she flaunts. The choice of siding against the ISIS is not a popular one among Jordanians, who would have preferred a more neutral approach in the nearby crisis zones. The Muslim Brothers are not the only ones to feel this way. But a choice had to be made because, apart from the threat of the ISIS, the Syrian civil war, the exponential spread of political and terrorist Islamic radicalism, the Hashemite reign is also involved in another dispute: that of Palestine. The confirmation of Benjamin Netanyahu, who claims that he will never allow the formation of a Palestinian state, in the recent Israeli elections is creating the basis for a new Intifada. In Jordan, where roughly half of the population is of Palestinian origin, such circumstance could be very dangerous for the stability of the reign. Then there is the problem of the Houthi and of the Saudi military attack in Yemen. Jordan supports the initiative publicly, but they fear that this new crisis could draw attention from the country’s absolute priority: the fight against the ISIS. From the start of the Saudi Yemenite campaign, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain have removed their aerial military support from the international coalition that fights the ISIS to use it in Yemen. Presently, Jordanian foreign policy tends to distinguish itself from that of many other regional actors: they are against the isolation of Iran; in the Syrian war, they’d rather see the fall of the ISIS than that of Assad’s regime; they are prudently critical of US disengagement in the region; they have welcome General Haftar from Libya, offering him arms and training. Only time will tell if the choices of king Abdullah have been wise ones. Yet one must never forget that, in the Middle Eastern context, Jordan is one of the weakest players, both in demographically, financially and militarily.