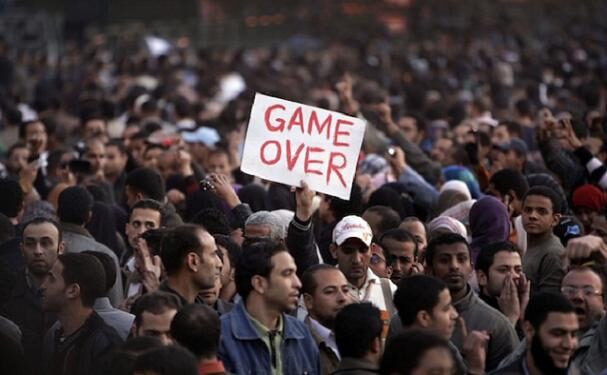

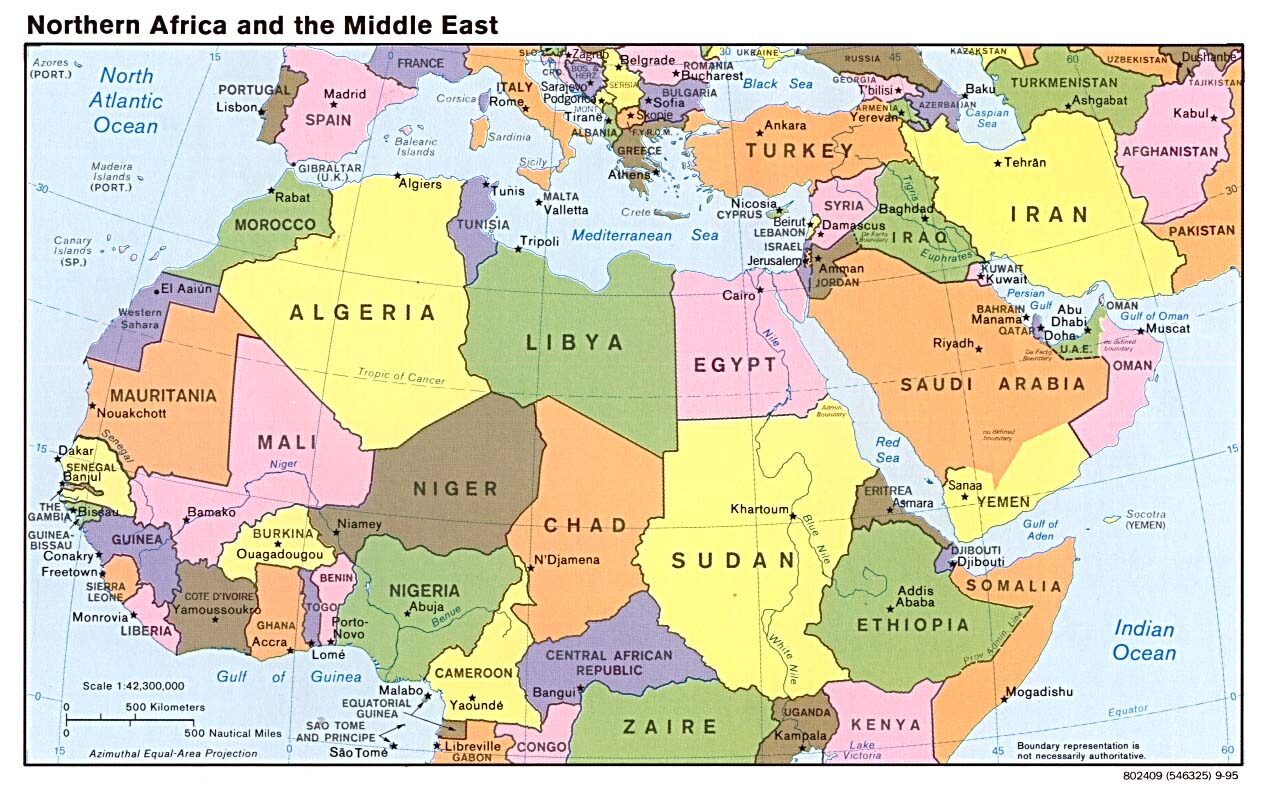

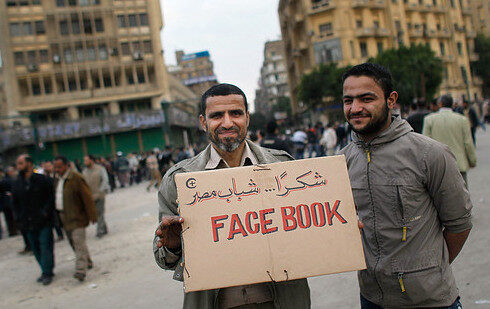

The series of events known as the Arab Spring spread in a temporal chain that has fueled its geographical propagation throughout several Arabic countries. A so called “domino effect” has made it possible for events happening in a single country (mainly social instability) to extend their effects onto bordering countries. This was possible thanks to the circulation of news globally as favored by mass communication tools (tv, internet, social networks etc.) linking causes and effects and eliminating barriers of both time and space. The social turmoil in the Arab countries developed and spread facilitated by the fact the these nations share common or similar social, economic and political characteristics. It is thus worthwhile retracing these events in their chronological order:

The series of events known as the Arab Spring spread in a temporal chain that has fueled its geographical propagation throughout several Arabic countries. A so called “domino effect” has made it possible for events happening in a single country (mainly social instability) to extend their effects onto bordering countries. This was possible thanks to the circulation of news globally as favored by mass communication tools (tv, internet, social networks etc.) linking causes and effects and eliminating barriers of both time and space. The social turmoil in the Arab countries developed and spread facilitated by the fact the these nations share common or similar social, economic and political characteristics. It is thus worthwhile retracing these events in their chronological order:

17 December 2010, Tunisia

Mohamed Bouazizi, a street vendor in Sidi Buazid, sets himself on fire in front of a local government office protesting against the ban to sell his goods on the street. Protests spread across the entire country.

29 December 2010, Algeria

The rise in food prices ignites a series of mass protests. In the following days 11 people try to suicide, 4 of them die.

14 January 2011, Jordan

After Friday’s prayers unions and left wing parties demonstrate against government policies in several cities across the country demanding for the Prime Minister to step down.

17 January 2011, Mauritania

In order protest against the President, a demonstrator, Yacob Ould Dahoud, sets himself on fire in front of the presidential palace.

17 January 2011, Oman

A few hundred protesters take the streets to demand higher wages and the decrease in the cost of living.

21 January 2011, Saudi Arabia

The Shiite minority protests in the Eastern regions of the country to ask for the liberation of its imprisoned activists. Even though it was a peaceful demonstration, the promoters of the rally are all arrested. They were all clerics.

24 January 2011, Lebanon

People take the streets to protest against the clerical power sharing system of the country.

25 January 2011, Egypt

Following a series of local and limited protests, the first mass demonstrations take place across several cities (mainly in Cairo, Alexandria and Suez). Two days later an assault will set fire to the headquarters of the National Democratic Party.

26 January 2011, Syria

A demonstrator, Hassan Ali Akleh, living in Al Hasakah, pours gasoline on his body and sets himself ablaze to protest against the Syrian government. Growing protests against the regime will follow day after day.

27 January 2011, Yemen

Over 15,000 people gather in Sana’a and several thousand more in other parts of the country to protest against the regime and, mainly and foremost, against the possibility that President Saleh hand is power over to his son Ahmed.

28 January 2011, Palestine

Protesters take the streets during the Hamas-Fatah talks.

30 January 2011, Morocco

Demonstrators ask for democratic reforms.

4 February 2011, Bahrein

Hundreds of people gather in front of the Egyptian embassy in a show of solidarity with the anti-government protesters in Cairo.

14 February 2011, Iran

Following the news from Egypt of Mubarak’s overthrow, protests in Isfahan degenerate into clashes and arrests. Similar demonstrations also take place at the same time in Teheran and elsewhere across Iran. Numerous opposition leaders are apprehended.

15 February 2011, Libya

A few hundred people protest in Bengazhi against the arrest of lawyer Fathi Terbil, human rights activist and attorney for the families of the detainees that died in the Abu Salim penitentiary. Security forces brutally put an end to the demonstration.

17 February 2011, Iraq

Rallies in Wassit, South of Baghdad, against the lack of electricity and water. Two government buildings are set on fire. Several people are wounded and arrested. Protests are also against corruption in government. In Sulemanyah, in Iraqi Kurdistan, demonstrators ask for reforms and protest against rising inflation. A protester is killed and 33 people are wounded.

18 February 2011, Kuwait

To prevent mass demonstrations asking for economic reforms, Emir Sheykh Sabah al Ahmad al Jaber al Sabah decides to lavish 4,000 $ to each subject of his rein (officially a contribution in the 20th anniversary of the country’s liberation from Iraqi occupation). The following day thousands of people take the streets to protest against such a waste of money and against the government lead by PM Nasser al Mohammed al Ahmad al Sabah.

ANALISYS OF THE EVENTS AND OF THEIR CHRONOLOGY The first observation is that the uprisings in the various Arab countries, even though closely lilted in time (and thus linked by a cause and effect relation), have different starting points: a social unease, an economic demand, a democratic request, a need for rights, a civil liberties protest, a fight by religious minorities. The domino effect is also in the forms of the protest: it is striking to witness the imitational behaviour that has lead to similar suicide attempts in Tunisia, Algeria, Mauritania and Syria. Another remark has to be made on the beginning of the demonstrations and the results they haven’t always been able to obtain. The different national struggles have thus had different outcomes: – in Tunisia a democratic process is underway in an overall peaceful manner, nothing has changed in Algeria (regardless of the fact that initially the protests were particularly violent) – in Libya a civil war has lead to a regime change, but has yet to bring to a social reconciliation – in Marocco popular requests have lead to Constitutional changes that have been peacefully piloted by the monarchy, – in Egypt the role of the military and its influence on the country’s political affairs has been replaced by a new theocracy-based leadership legitimated through an election, – in Mauritania small economic concessions have toned down the demands from the street, – in Yemen President Saleh has been dismissed without further bloodshed (to note the Saudi role in the negotiations and the fact that all popular demands have disappeared with the regime change), – in Syria the government entrenched on radical positions using violence and allowing for a civil war to take place, – in Jordan protests have lead to the fall of the Government, but the demands for greater Constitutional freedom has turned the struggle into a clash between pro-monarchy and reformists, – in Lebanon demonstrations asking for a different institutional framework were overcome by the concerns over events in Syria and the potential repercussions home, as the recent killing of the head of the internal Secret Service Wassan Hassan has shown, – in Saudi Arabia the Shiite rebellion was crushed by force and the demands for more freedom have been repressed with little gains (note the promise for women’s right to vote), – in Oman economic requests from the population were initially repressed by government, but were later granted since no one was questioning the authority of Sultan Qabus, – in Iraq the endemic instability of the country has not allowed any room for economic requests, social petitions or adequate reforms (regardless of the fact that on December 15 2011 the US officially withdrew from the country), – in Iran the struggle between reformists and conservatives, the tension between Khamenei and Ahmadinejad and among clerics and secularists have all watered down the requests coming from civil society involuntarily transforming them in an internal power struggle to the regime. The Security forces have all had a freehand in repressing the protests, – in Bahrein the Shiite uprising was solved manu military through the intervention of Saudi and Emirate units deployed to protect the Sunni regime of Hamad al Khalifa, – in Kuwait protests have lead to the dissolution of Parliament, – in Palestine the agreement between Hamas and Fatah has defused protests and contrasts even though the animosity between the two conflicting souls of the Palestinian diaspora is still ardent,

In all the above cases there has been no correlation between the level of violence in the protests and the quality of the results achieved. As a matter of fact, there is a marked correlation between the repression operated by regimes and the consequent limit in the gains obtained. This element is more evident if we consider that we are facing, in most cases, authoritarian regimes who have made an indiscriminate use of force. Another remark can be made on the fact that the regimes lead by monarchies legitimated by religion have been by far more capable in facing the social turbulence of the Arab Spring. This has been the case in Morocco (Alawi monarchy), Oman (Ibadite sultan), Saudi Arabia (Wahabi monarchy), Jordan (Hashemite monarchy) and to some extent in Iran’s theocracy. On the other hand, military regimes (Syria, Egypt, Yemen) have shown a lack of suppleness during negotiations and have all been involved in bloody repressions of dissent. A last remark should be made on the achievements obtained by popular demonstrations in Arabic countries. Putting Tunisia and Egypt aside (and Libya despite the external intervention), in other Arab nations, whether we are dealing with social and/or economic and/or political demands, a lot was asked for by protesters, but little has been achieved. The answer to this issue has to be found by focusing on the social context in which the protests took place. In fact: the miscellany, within the different national demonstrations, of both civil liberties and economic requests has penalized the first with respect to the latter and hence, prosaically, the obtainment of economic advantages has often defused the protests. A common denominator was lacking, both within the individual national demonstrations and in the Arab world as a whole. The domino effect was hence triggered by a common will to protest, not by common demands. As a consequence, the propelling push of the Arab Spring was dispersed in the specificity of national demands; overall the people of the Arab world lacked the consciousness on the aspirations and demands that are acquired only through a lengthy process of democratization of society. In the countries we are examining democracy is not a comparative value because the process has never started. Most nations went from the colonial phase onto the post-colonial one mostly ending up under authoritarian regimes. A democracy that has never been experimented cannot turn into a value, its advantages and limits are unknown, individual imagery is not sensitive to it. What mass media spread through global communications and news can feed the Arab with the concept of a society different from his own. But this is more on aesthetickal terms, rather than having to do with civil liberties. And when you are not sure about what you want, it is difficult to ask for it or to obtain it or even, if it be the case, to allow for it; the kind of society the Arab protesters yearn to obtain after the revolt is not much different from the one they are fighting against. In most cases they are after a regime change. And were they to obtain it, the new regime would maintain the very same behavioral limits that characterized its predecessors: authority wielded with the use of force, the poor attention for opponents and protesters, the negation – if necessary – of those inalienable rights that are part of any social and democratic context. In other words, the demonstrators are after a regime change, but do not pose themselves the question (since they are lacking specific cultural experience on the matter) on how to shape the new one. On this subject their models are definitely limited. It is possible that after Khadafi’s dictatorship a new authoritarian and scarcely democratic form could take over. When trying to figure out a new model for society, Arabs tend, on the basis of their past experience, to assimilate the management of power with the use of force and not, as would be desirable, on the search for consensus. What is defined in the Western world as “public opinion”, meaning the common feeling of the population and the will of the majority of the people, is another of those reference values lacking in most participants in the Arab Spring. Public opinion is identified in our fellow protester, but does not include the possibility that another public opinion could contrast my ideas. Thus, overall these remarks postulate that the so called Arab Spring did not produce a significant benefit to the spreading of democracy, intended as a universal value. We should also consider that any regime change, if obtained abruptly, through force and not through a slow process of assimilation, will generate instability. And this is potentially the major risk associated with the wave of protests of the Arab Spring. Until now, where change has been radical, firstly in Libya and to some extent in Egypt, peace and social security have been jeopardized. With the sole exception of Tunisia (that does not set a standard) due to a set of peculiar reasons (it is one of the most socially advanced countries in the Arab world, it is subject to a strong European influence also through tourism and has benefited from a charismatic leader). Tomorrow if the same process should take place in other Arab nations, we have to expect more social problems than solutions. We could ask ourselves the question whether it is good or bad that some Arab Springs did not achieve their aims. The Arab Spring, in its definition, implies an awakening of the conscience of the people in the Arab world and of their search for justice and freedom and should hence constitute, on the theoretical level, a positive event. If, in practice, this circumstance has been emphasized, lesser attention has been paid to the implications the Arab Spring could have on the stability of the Middle East and North Africa, on the oil market and the control for gas pipelines, on the clandestine migrations flows, on a geo-strategical context divided among conflicting spheres of influence, on the military balance among countries in the region, on the conflict between Sunnis and Shiites and, as a consequence, on the security of the Christians, on the protection of the maritime routes in the Gulf and through the Suez Channel, on the spread of terrorism fueled by the growing instability in the region, on the safeguard of national borders and of entities drawn on a map by colonial and post-colonial powers, on the impact on the financial markets of the immense capitals deriving from the sale of energetic resources, on the daily life of an ordinary Arab who expected an improvement in terms of liberties and security and which he will probably not obtain.