After the death of Mohamed, Islam made its entry into Africa following military conquests, but without shattering effects. When the prophet passed away in 632, the first islamic Caliph, Abu Bakr, carried out a series of military operations to spread the new faith across the world. Even though the latter died two years later, his nephew Omar continued the ambitious military expansion program with the conquest of Jerusalem (636), then of Damascus, Antioqchia and finally of Persia in 651. The arrival of Islam on the African continent came about in 646 with the conquest of Egypt. As stated earlier, it is a tolerant and apolitical Islam that initially respects African societies, their customs, traditions and rituals (even the animist and pagan ones), without undermining the structure of societies centuries-old that pre-existed on the continent. It is hence a penetration that did not cause any traumas, but actually found a fertile ground in the exoteric tendencies of those people. African Islam is syncretic, simple and tolerant, miles away from the learned and cultivated Arabic Islam, almost a deformed version of the latter. Islam’s diffusion was then limited with the arising colonialism in Africa and by the competition between civilizations that also involved religion. Today the muslim religion is distributed across the continent along a political and social itinerary that is spread mainly throughout the North and the Coastal areas of Africa. But African Islam, at least in the beginning, was moderate and spiritual and it easily went along the spirituality and fatalism of Africans, it supported their ritualism and associative will.

After the death of Mohamed, Islam made its entry into Africa following military conquests, but without shattering effects. When the prophet passed away in 632, the first islamic Caliph, Abu Bakr, carried out a series of military operations to spread the new faith across the world. Even though the latter died two years later, his nephew Omar continued the ambitious military expansion program with the conquest of Jerusalem (636), then of Damascus, Antioqchia and finally of Persia in 651. The arrival of Islam on the African continent came about in 646 with the conquest of Egypt. As stated earlier, it is a tolerant and apolitical Islam that initially respects African societies, their customs, traditions and rituals (even the animist and pagan ones), without undermining the structure of societies centuries-old that pre-existed on the continent. It is hence a penetration that did not cause any traumas, but actually found a fertile ground in the exoteric tendencies of those people. African Islam is syncretic, simple and tolerant, miles away from the learned and cultivated Arabic Islam, almost a deformed version of the latter. Islam’s diffusion was then limited with the arising colonialism in Africa and by the competition between civilizations that also involved religion. Today the muslim religion is distributed across the continent along a political and social itinerary that is spread mainly throughout the North and the Coastal areas of Africa. But African Islam, at least in the beginning, was moderate and spiritual and it easily went along the spirituality and fatalism of Africans, it supported their ritualism and associative will.

Sufis in Sudan

SUFI CONFRATERINITIES The best reply to the moderate needs of Africa came from within its social texture with the development, more than anywhere else, of Sufi Confraternities. From an historical point of view, they emerge in the Middle East during the 12th century and then spread in Africa. The name “suf” comes from the camel wool clothes the Sufis would wear to show their devotion to a mystic life. The other name given to the members of the confraternities was “dervish”, a Persian word meaning someone who gives up earthly issues to dedicate his life to God. According to several historians, the origins of Sufi mysticism, hence before it was structured into confraternities, dates back to the 8th century. Following the numerous military conquests and growth of the wealth of the Omayad Dynasty, Islam was at risk loosing its original ethical connotation. People like Hassan al Basri (642-728), Rabia al Adawiyah (d. 801), al Hallaj (sentenced to death in 922 after 8 years of imprisonment) dedicated their lives to criticizing muslim clerics and preached the union with God through the love of God. In practice, sufism developed a mystical approach to Islam as opposed to a legal/lawful vision of muslim orthodoxy and this favored its development in Africa. They preach the possibility of an emotional nearness to God and an intuitive knowledge of God through faith, far away from the intellectual and legal emphasis of Sunni orthodoxy. In this sense, Sufis interpret the Koran as the key to determine a mystic union between the individual and God. This is why every Order imposes to its followers (known as “mourids”, Arabic translation for “he who accepts” or “he who is devoted to a faith”) a close personal relationship with God through strict spiritual discipline. The prayers (“dhikir”) involve exercises that are accompanied by movements of the body, including chanting and dancing, according to a formula established by the founder of the Order. By doing so, when the litanies are particularly long, the believers fall into a trance and reach an ecstasy whose aim is to free the body and bring it to the presence of God. How they pray (“tariqa” or “via”) varies from one confraternity to another and they are identified by their “tariqa”. Each tariqa, besides having its own ritual, also has an internal organization that can ben, according to the Orders, more or less hierarchical. And this is a hierarchy that substitutes the clan or the ethnic groups of origin. By doing so it creates a social alternative to African tribalism. There is a chief responsible for initiating new members and that delegates some responsibilities to the other levels. Joining a confraternity is voluntary even if family traditions and ties from father to son often prevail. The novices take an oath of loyalty to the chief of the confraternity. The chiefs’ title is that of Sheykh (doctor of Islam) and they are believed to own the “baraka”. The latter is a “supernatural blessing” that implies a spiritual power during the exercise of the religious activity. But there is more to it: it is a set of positive personal characteristics, both moral and intellectual, in possession of only some individuals. This spiritual status can continue even after death, thus generating the status of “holy man” whose worship goes beyond the belonging to a specific confraternity. This is why several tombs become pilgrimage sites. In the same way the earlier chiefs of the confraternity are venerated in order to grant the “baraka” a sense of continuity. Also those who are responsible for the spreading of the religious creed are accredited with the same blessing: the “marabout” in Western Africa and the “wadaddo” in Somalia. The “marabout” (transliteration of “al morabitoun”, namely “those who have built a religious shelter”) are the intermediaries between the individual and God and they officiate islamic services. Until today they constitute an errant system for the spreading of Islam. Beyond the teaching of the Koran and the cultural promotion of Islam, the “marabout” favors proselytism, spreads the faith, may involve in politics, officiates rituals and duties to cure people (he is accredited with mystical powers to protect from ailment and evil eye), intervenes in the mediation of conflicts (negotiations, peace treaties between faction in fight), acts as a consultant (also a political one) for tribal chiefs, grants protection and asylum and sells his amulets and talismans. Earlier on it was a general opinion that the “baraka” could apply only to the descendants of Mohamed. With the advent of Sufism and the creation of the confraternities its application went beyond that and onto anyone who had the right characteristics. Sufism also introduced another crucial concept: the acceptance of an intermediary between us and God. This gave birth to the confraternities and to the recognition of the existence of “holy men”. Generally speaking, the members of the confraternities live a secular life within their communities of origin. Seldom they reunite in enclosed communities (known as “jama’a”) to undergo indoctrination. Only a few are celibates. We’re dealing with mainly spiritual communities rather than practical ones even if there is a designated territory (“zawiya”) where the confraternity operates. The mystical aspects of Sufism have favored in Africa the fusion between the Islamic belief and the pre-islamic ones. Taking as an origin a combination of Sufi mysticism and Sunni orthodoxy, the Islamic fraternities have constituted a unifying factor between culture and religion outside ethnic and tribal differences. The other role undertaken by these Orders was the contrast of Western customs. As mentioned earlier, the first Sufi confraternities date back to the 12th century (the “Rifaiyyah” founded in Basra and that spread from Iraq, to Syria and Egypt; the “Suhrawardiyyah”, founded by Abu Najib al Suhrawardi (1097-1168), that grew in India; the “Kubrawiyyah”, founded by follower of Suhrawardi, Nayim Al Din Kubra (1145-1221) in Iran; the “Qadiriyyah” that developed in North Africa). In Africa the first Sufi confraternity appeared in Egypt and came from Syria as an expansion of the “Rifaiyyah”. The founder was Ahmad al Badawi (1199-1276) who became renown for his miracles. Until today in Tanta, Egypt, every year a festival pays tribute to the “Badawiyyah”. In North Africa Sufism spread thanks to the support of the Almohad dynasty (1130-1269) that ruled over Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and part of Spain. In the 13th century in Tunisia a man by the name of Shadhili founded the “Shadhiliyyah” and it can still be found in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. In the 18th century a new twist in the evolution of Sufism came about when it clashed with the rising Wahabism that refused several Sufi traditions, like the worshipping of saints, and favored a strict application of Sharia law. As a consequence, new orders were born like the “Tijaniyah” and the Sanisiyah”. Here is the description of some of the Sufi confraternities that have had a preeminent role in Africa:

The Qadiriyah

It is the oldest Sufi order and it was founded by Abdel Qadir al Djilani (1077-1166) in Iran and later moved to Baghdad where Djilani ran the Hanbali law school. In the 15th century the order developed in Africa under the guidance of Osman Dan Fodio (1754-1817) who dedicated his efforts to the eradication of tribal practices during islamic rituals. Fodio worked in today’s Niger and Nigeria. As many other confraternities, the Qadiriyah includes both emotional and mystical elements, but also pursues the teaching and knowledge of Islam as a way to find God. Every member of the confraternity has to follow the precepts of humbleness, generosity and respect for thy neighbor regardless of their religious creed or social status. The Qadiriyah was deeply involved in the Algerian independence struggles against the French.

The Tijaniyah

It was founded in 1781 by Ahmad Tijani, an Algerian berber who died in 1815. Its ritual (or method of recitation) is more simple and flexible if compared to the Qadiriyah even though both share the same doctrine and religious obligations. As opposed to the Qadiriyah, its members don’t necessarily have to develop Islamic teaching and, with respect to the other confraternity, it is considered fitter to accepting a modern way of life. The precepts of the confraternity impose the refusal all falsehood, theft, killing and fraud. Furthermore, promises should be kept, love thy neighbour and obey God. No member should deprive others of freedom without a reason. During prayers one should be mirrored in God. Even though we are all sinners, the Tijaniyah believes that the members of the confraternity will be rewarded after death. As opposed to other confraternities, the Tijaniyah does not allow the simultaneous belonging to other Orders. They impose a religious separatism from the other confraternities. It is unlikely that a member leave the organization in the belief that the betrayer will die as an apostate. The Tijani think of themselves as sort of the aristocracy of the mystic orders and self define themselves as “al tariqa al Mohammediyah” (the path of Mohamed). Ahmad Tijani claimed to receive revelations directly from Mohamed himself and became known as a “qubt al aqtab” (the pole of poles). The Tijaniyah resembles a missionary order that spread across West Africa to the detriment of the Qadiriyah. When Tijani died in 1815 several conflicts emerged between the different “zawiya” of the confraternity that caused the fractioning of the order.

The Sanusiyah

Founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Algerian Mohamed Ibn Ali al Sanasi from the Senusi tribe, born in 1787 and who proclaimed being the descendant of Fatima,. Sanasi studied in Mecca and founded several “zawiyas” (communities). While in Libya, he developed his activity mainly in Cyrenaica organizing the beduin tribes in Fezzan and Kufra. Among the different confraternities, it’s activity is the most politically oriented. Its “zawiya” was initially in Jaraboub professing a purified Islam that adapted to the lifestyle of the nomadic people of the desert. It preached the respect of the precepts of the Islamic religion (with a certain degree of behavioral fundamentalism like the ban of the use of tobacco) and during its rituals it aims at a mystical union with the Prophet rather than with God. The union is meant to imitate the daily life of Mohamed. The history of the Sanusiyah intertwines with that of Libya. When al Sanasi died his son, Mohamed al Mahdi (born in 1859 and whose rule lasted until his death in 1902), took over and extended the confraternity’s influence in the area of Lake Chad. His wealth also grew thanks to his trading across the Sahara. As both the French in Chad and the Italians in Libya advance, the confraternity waged a conflict against the colonial powers. During World War I, Al Mahdi’s successor, Ahmad al Sharif, brought forward, without much success, a policy siding with Turkey. When Idris took over the confraternity, a deal was initially struck with the Italians, but it was broken in 1923. When the armed struggles against the occupiers began, the leader of the confraternity are forced to flee in Egypt where they will support the British during World War II. From 1951 to 1969 (before Gaddafi’s coup d’etat) the Senusi dynasty ruled over Libya. The Sanusiyah can count on around 350 “zawiya” spread across Africa (mainly in Morocco and Chad) and as far as Indonesia.

The Mouridya

founded by Amadou Bamba (also known as Mohamed ben Habit Allah, 1852-1927), the confraternity has its geographical center in Senegal and Gambia. Ideologically it is half way in-between the Tijaniyah and the Qadiryah. Bamba was considered an innovator. Under the guidance of a Caliph (or Great Marabout) with absolute powers, the Mouridya is structured into regional marabouts. Its economy is linked to the manual labor of its followers and it is self defined as “a way to imitate the Prophet”. Streaming out of this confraternity others are born like the Baye Fall of Sheykh Ibrahim Fall.

Ibn Taymiya’s grave in Damascus, Syria

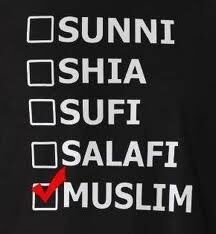

SALAFISM In contrast with Sufism’s moderate approach, the Islamic world developed – in Africa and elsewhere – a tendency to embrace radical religious behaviors, an orthodox vision and interpretation of the precepts. Salafism, whose origin is the Arabic word “salaf”, meaning “forefathers/ancestors”, proposes a return to pure Islam, meaning the one immediately following the death of the Prophet and thus considering that what happened throughout the centuries following foreign occupations and contamination with the Western world lead to a loss of the original characteristics of the religion. The warrantors and advocates of a pure Islam are those that implicate an ideological recourse to “jihad” as both a defense (of the Islamic nation) and offensive (against an external contagion) tool. This is an evolutionary doctrine that provides the muslim fundamentalists an alibi in the fight against modernization, the decay of customs and globalization and that today, in its most deleterious forms, postulates terrorism. From an historical point of view, Salafism originates from theologian Ibn Taymiya, follower of the Hanbalist school (founded by Ahmad Ibn Hanbal in the 9th century) that refused the use of rational methodologies in the interpretation of the Koran and of the Sunna: divine elements could not be understood through a rational approach. Based on this assumption, Ibn Taymiya became a supporter of an individual interpretation of the sacred books. An innovative stance at his times because it meant that the spreading of the religion could become more popular and off the reach of the elite in power that until then had taken care of the theological and social aspects of Islam. Yet Ibn Taymiya demanded the obedience to the political chiefs and fought against any theological deviance that his new interpretative approach may have determined. During the 18th century also Mohamed Ibn Abdel Wahab (the founder of Wahabism) joined Hanbalism to look for pure Islam and, after him, the Iranian Jamal al Din al Afgani (1838-1897), the Egyptian Mohamed Abdul (1849-1905) and the Syrian Rachid Redha (1865-1935). Together they gave birth to a new Salafi current that lead to the defenestration of the clerical structures of Islam. With the creation of the association of the “Muslim Brotherhood” by Hassan al Banna in Egypt in 1928 Salafism took a political twist, that is to say Islam had to be reorganized to take over power. In the 50s another Egyptian and member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Sayed Qutb (1906 and sentenced to death by Nasser in 1966), theorized about the rise to power that would overthrow the impious Arab chiefs and reinstate an Islamic State through armed struggle. Qutb will become the point of reference for several terrorist movements, not least Al Qaeda. To date there are three main tendencies within the Salafi movements: a moderate Salafi approach that refuses political Islam, it is against violence, boycotts elections and considers attacks and “shahid” (martyrs/suicide bombers) as being illegal; reformist or modernist Salafism, close to the thesis of the Muslim Brotherhood, that subordinates politics to religion and finds in the Koran the justification of their objective; a so called “jihadi” Salafism that refuses preaching and exalts the holy war against both the muslim world and the West; this is an individual struggle that refuses all political approaches.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF ISLAM AND ITS EFFECTS IN AFRICA

Overall, Islam is a simple religion, scarcely dogmatic and, as such, easily assimilated by any cultural and social level. This also applies to Africa. There are five pillars to the religion: “shahada” the declaration of faith, “salat” the five daily prayers, “zakat” the yearly handout of charity, “saum” the month of fasting during the Ramadan and “haji” the at least once in a lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca. On the dogmatic level, there is one God (“tawid”) and one Islamic community (“umma”). The soul is immortal and Mohamed is considered the last Prophet (the so called “seal of the prophets”) after Adam, Noé, Abraham, Moses and Jesus (the Koran does not abolish Jewish or Christian revelations, but rather completes them putting the final seal). Angels exist (look at the role the Archangel Gabriel has for Mohamed), the Koran is the last holy book and we should all expect a judgment day (similar to the Christian one, but with some peculiar divine pleasures). The “shura” (verses) of the Koran and the “hadith” (teachings of the Prophet) of the “sunna” (the tradition) are the only elements of theological inspiration that can be subject to interpretation. There is no religious hierarchy in Islam (there is a clergy, but no priesthood or sacrament), but only juridical schools. And it is often in the interpretation of the holy books that both fundamentalism and extremisms find their origin. In fact, concerning the interpretation of the sacred texts and the possibility of their exploitation, there are two main schools of thought in Islam: the “taqlid” whereby the interpretation has to fall and be applied within the existing islamic doctrine; the “itjihad” whereby the interpretation is dealt with individually. Mainly the latter often provides the basis to justify the theology of terrorism. During his earthly life, Mohamed had created a theocratic State in Medina that ruled over the “umma”. And it is in the overlapping of secular and spiritual power that Islam finds its root. Unlike Judaism and Christianity, the muslim religion is based on the strict interdependence of politics and religion that increases the social impact of the latter on the affairs of people. If the Christian God is the one of love, the Jewish God is that of justice, the Muslim one is mainly a social God. That is, Islam introduces a concept of “statehood” that is not that of a theocracy, but it is linked to the interdependence between the preaching and application of Islamic precepts and the legitimacy of power. The lacking of democracy in the African continent makes such a precept easily receivable. Islam also introduces other specific characteristic as divine decree and predestination. At a popular level, predestination is a widely diffused concept that includes the belief that everything that happens in a lifetime is God sent and that any attempt to change events is useless. It is a dimension of power and/or wisdom and/or mercy of God that postulates a concept of fatalism (even though also Islam adds individual responsibility to the equation). It is not accidental that both “Islam” and “Muslim” (same consonant root) introduce the concept of submission to God. The prostration of the muslim to God’s will, or rather predestination in Sunni orthodoxy, does not have the same philosophical or spiritual characteristics of its Christian equivalent. Fatalism introduced by Islam is another one of those concepts easily accepted by people in Africa who have lived through centuries of social calamities and hardship. Furthermore, predestination could also affect the sense of development and modernization of Islamic societies that appears more limited if opposed to the Western approach to progress (and this also complies much more with African societies). This determines a gap between the two worlds and when, as in the current political conjuncture, comes a comparison, it turns into a clash of civilizations, a fight not only between Christians and Muslims, but also between the respective visions. Yet, there is an ongoing and hardly publicized clash between moderates and radicals within the muslim world. Finally there is one last concept, that of divine justice. God is “good” and what it does is “right”. But God is above right and good or evil and is not bound by justice. God is neither obliged nor obligable. There can be no injustice because everything belongs to Him. Hence God can do what he wants. There is no relationship between good behaviour and earthly justice. The divine prize will come in the after life. Africans face a hard, even though not deserved, present but no one enquires whether this is right or wrong. Islam thus becomes a social tool where rights and civil liberties are denied or where poverty claims more justice, though at last the hope in a better future in heaven can bring us to easier terms with the misery in the present. Another aspect that has made Islam tempting to African people is the tolerance towards some social aspects of indigenous cultures, like multiple marriage (a practice refused by other monotheistic religions).

Salafist group for preaching and combat

CONSEQUENCES OF RADICAL ISLAM

Sufism and Salafism have been the ingredients that, in different doses and ways, have influenced events in Africa in those countries with a majority or strong presence of muslims. Over the last few years, Salafism and its religious radicalism – which then turned into extremism – have taken the upper hand over moderate islamic stances. Social injustice, totalitarian regimes, widespread poverty are constant in the African political landscape and have all helped the rise of radicalism. Salafism has inspired several terrorist movements across Africa: the Jihad Islamiyah e la Jamaa Islamiyah in Egypt, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat in Algeria, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb along the sub-Saharan Sahel, the Islamic Combat Group in Libya, the “talebans” and Boko Haram in Nigeria, Al Ittihad al Islami, the Islamic Courts and the Shabaab in Somalia, Al Qaeda cells in the Comoros, the “Allied Democratic Front” (infiltrated by Al Tabligh extremists) in Uganda, the Moroccan Islamic Combat Group in Morocco, the Tunisian Islamic Front (and the Ennadha party ran by Rachid Gannouchi during the fight against Ben Ali) in Tunisia, the (subversive) activity of the Haramain Islamic Foundation in Kenya and Tanzania, the PAGAD (People Against Gangsterism and Drug) and the Qibla (of Shiite inspiration) in South Africa. And the listing could continue. According to statistics, in 2011 the world has witnessed 1974 terrorist attacks by Islamic radicals that have caused over 9000 deaths and 17000 wounded. The trend is growing and Africa is more and more present. Muslims in Africa are 370 million, as opposed to 305 million Christians and 137 million following indigenous religions. Hence, they are now the majority in the continent. Yet, from an historical point of view, the spreading of Islam in Africa would not be an element of interest hadn’t it been for the improper use of religion in international affairs and in the contemporary history of several countries across the continent. We’re talking about the rise of the so called Islamic fundamentalism, that in the worst cases turns into extremism and then terrorism. In Africa, limited to certain areas or countries, this negative social phenomena is both an endogenous (if we look at what happens in individual countries) and exogenous (the afore mentioned clash of civilizations) factor. With respect to other parts of the world, Islamic extremism in Africa is potentially more dangerous, not for what it is today, but for what it could turn into tomorrow. Such an evaluation is tied to a series of objective circumstances such as: the condition of poverty of the majority of African people could potentially witness the use of Islam as a tool for social change; the lack of fair regimes and/or democratic ones could pave the use way for the use of Islam as a tool for political change (see what the Muslim Brotherhood is doing); the strong spirituality of African people could see the use of Islam as a social placebo; the search for a common cultural identity capable of unifying ethnic groups or tribes across the borders could witness the use of Islam as a tool for ethnic identification; the need of a de facto fatalism to face negative living conditions due to famine, poverty or malady could see the use of Islam as theological placebo. All of the above fall into a continent where weapons are widespread, corruption is rampant, where there are plenty of wide spaces where to move undisturbed and without control, with little or fable technological support. These are all factors that can amplify the devastating effects of terrorism. What worries the most is the prospect that African Islam could become more and more associated to social instability along the afore mentioned factors. Not merely linked to events in North Africa, as has happened during the “Arab Spring”, but geographically extended to other sub-Saharan areas. Another element of concern is the currently ongoing welding between the different African Islamic fundamentalist groups whose negative influence is moving from a country level to a regional one and, maybe in the future, to a continental level. In other words, we could be in a phase where Islamic terrorism seizes a local social issue (and it wouldn’t be hard to find one) to legitimize its operations to then moves onto wider issues and geographical contexts. Today we face a territorial contiguity between Somalia, the groups operating in the Sahel and those in North Africa. And it is probably not by chance that Al Qaeda, since the Osama Bin Laden days, has addressed its geo-strategic aims onto Africa (Bin Laden lived in Sudan in the 1990s, where he had made important investments, and transited in Somalia before moving to Afghanistan).