THE WORLD’S CALIPHATES

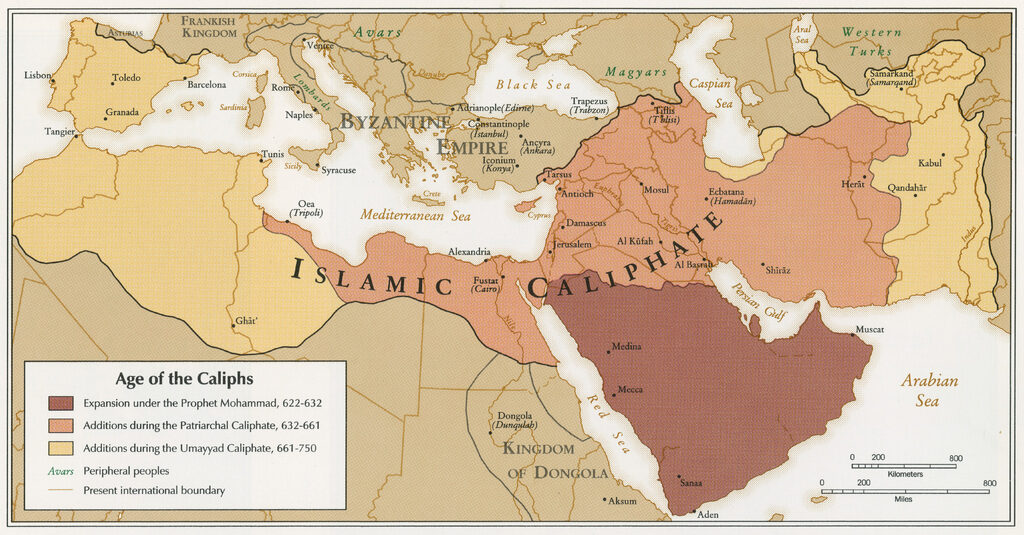

The birth of a caliphate, as proposed by Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, is a piece of the history of Islam that followed the death of Mohamed. The caliph or “successor” was the political and religious guide, combining both spiritual and secular powers. He carried forth the Prophet’s agenda and the expansion of Islam around the globe. Historically, the days of the caliphs were an epoch of territorial conquests.

Zarqawi vs Baghdadi

It is not a coincidence that Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al Badri al Samarrai, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s real name, has a tendency to identify himself and his territorial gains with this specific part of the history of Islam. He picked up Abu Bakr’s name because he was the first caliph and father-in-law of Mohamed. He then added the “Al Baghdadi” attribute to identify where he comes from or, possibly, to declare what his main target is. Another possibility is that, given that his predecessor in the fight against the Iraq’s Shia leadership was the now defunct Ahmad Fadeel al-Nazal al-Khalayleh, also known as Abu Musab al Zarqawi (Zarqa, in Jordan, was his hometown), Abu Bakr decided to also include a city’s name in his last name. The reference to caliph Abu Bakr is also a clear referral to a caliphate that within a short time span was marked by a series of victories against apostasy, expanded the Umma – the Islamic community – and was led by a man that despite being rich lived a humble life. If Abu Bakr’s was the first caliphate, the last one was the Ottoman Empire, that lasted from the fourteenth century until it was abolished in 1924 when the empire dissolved. Zarqawi fought against the Shia government in Baghdad and against the US occupation that followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This objective was contained within the Iraqi boundaries. Al Baghdadi, instead, has raised his stakes: he wants to establish an Islamic State beyond the border of Iraq and, rather than fighting against the infidels (the US and the other nations participating in the international coalition), is targeting the apostates, be they Sunni or Shia, that do not adhere to his project. Both Zarqawi and Al Baghdadi have used terrorism and have some similarities in how they employ or exploit terror. The difference is that Zarqawi’s Jama’at al Tawhid wal Jihad was confined to the Iraqi events of its time, while Baghdadi’s ISIS was formed in Syria and then spilled over to Iraq.

The franchising of the caliph

Al Baghdadi’s project is definitely ambitious, with messianic undertones, a dream like the ones the caliph Abu Bakr knew how to interpret. Yet his reverie, thanks to his organization, the mystical elements contained there-in that take us back in time to the dawn of Islam and the aim of creating an independent territorial entity, has led to the proliferation of self-proclaimed caliphates around the world. This is the same franchising effect and imitation game that took place when Al Qaeda was at its peak of fame and success under the leadership of Osama bin Laden. But it is also clear that the newborn caliphates sprang up in most cases where regional conflicts were already ongoing. The affiliation with the ISIS only came at a later stage. And if the name in the background has changed, the targets of the revolutionary actions have not. This implies that the new caliphates have become a tool of propaganda to establish a new trademark. The media hype around the ISIS due to its ruthlessness has made the rest. Now everyone wants to be part of a global struggle in the name of religion, a war worth fighting and dying for. What brings the ISIS and the other caliphates together is the transhumance of terrorists roaming around the world from one crisis zone to the next, anywhere they can exercise their destabilizing activities. And this is a recurrent circumstance in the Middle East and Africa. In this hunt for proselytes, the brand of the ISIS has become a celebrity and is bound to take over once prestigious labels such as Al Qaeda.

There is still some ongoing competition between the two terrorist brands. In Syria, for instance, Jabhat al Nusra, Ahrar al Sham and Khorasan claim that they are affiliated with Al Qaeda; Harakat Sham al Islam and Suqour al Izz have joined the ISIS instead; Ansar al Islam, after an initial clash with the ISIS, has decided to remain equidistant. There is also the possibility that both terrorist brands will decide to abandon their rivalry and merge in the near future.

Abu Sayyaf in the Philipines

The blossoming of the caliphates Over the last few months, more and more caliphates have been proclaimed. In some cases we are talking about mere jihadist cells that have expressed their allegiance to the ISIS without having any real ties with Baghdadi’s organization. But just where are these caliphates? Well, there is the one established by the Tehrik i Taliban Pakistan, the Pakistani talibans, along the border with Afghanistan, ISIS flags have surfaced in Kashmir (on the Indian side of the border) and in Waziristan (the tribal area between Afghanistan and Pakistan). To confirm this trend, a recent attack in Jalalabad in Afghanistan that killed 34 people was claimed by the ISIS. More countries and single terrorist cells have also joined the domino effect in Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Chechnya and the Chinese region of Xinjiang. Even an historical terrorist group on the scene since 1991, like Abu Sayaf’s Harakat al Islamiyah in the Philippines, has also declared its affiliation. The strong ties with the ISIS are a direct consequence of the presence of Afghan and Pakistani veterans in the ranks of Al Baghdadi’s militias. The biggest threat from the expansion of the ISIS, or rather of its ideology and modus operandi, comes from the Middle East and Africa. In the Sahel two AQIM factions, Jund al Khalifa, led until its leader’s death in January 2015 by Abdelmalek Gouri, and the one under the command of Mokhtar Belmokhtar, have both joined the ISIS. So have the Shabaab in Somalia and, foremost, Boko Haram in Nigeria. Endemic poverty, the absence of civil liberties and of any hope for a better life make of Africa one of the largest potential breeding grounds for the ISIS. In North Africa the most prominent group is the Egyptian Ansar Beit al Maqdis, that has established a caliphate in the Sinai peninsula. They have strong ties with a number of terrorist groups in Egypt, like a newborn faction that has surfaced in January 2015, Agnad Misr, and that is probably a splinter faction of the Jihad Islamiyah. Another affiliated group in Egypt are the Al Furqan Brigades. A similar scenario is taking place in Tunisia and Yemen with Ansar al Sharia, whose local branches have publicly announced their ties with Al Baghdadi. In Morocco and Jordan words of allegiance have come from single terrorist cells. But, as we’ve said, most of these terrorist groups have expressed a mere political affiliation with the ISIS.

Libya is a different case altogether. The self-proclaimed caliphate established in Derna blossomed after the ISIS was formed, since no terrorist group was allowed to operate freely in Libya so long as Muammar Khadafi was around. A decisive role was played by the Ansar al Sharia fighters and their recently killed leader Mohammed al Zahawi. Key elements in this caliphate were also a brigade of Libyan veterans that returned from Syria and joined the Al Battar Brigade. In this case the ISIS played a role in the establishment of the local caliphate, as the appearance of the ISIS in Sirte indirectly confirms.

Polisario in Morocco

Future developments The main question we should pose ourselves is whether, apart from a common branding, there are operational ties between the different caliphates around the world. To date this does not seem to be the case. As an Egyptian commander from the Beit al Maqdis has recently explained, the communications with the ISIS take place over the internet. Ideas are shared, methods are discussed, behaviours may be imposed, but each group still maintains its own independence. The same approach is used when it comes to exploiting the media to publicize an attack: the echo will be larger if the right label is used. The real danger from the expansion of the ISIS’s fascination in the Islamic world is not the proliferation of caliphates per se, but rather the effects the success of their aggressive military strategy may have in the decision-making process of other radical groups. It may well be, for instance, that the Muslim Brothers, oppressed in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, marginalized in several countries in the Gulf, could decide to share a common agenda with the Beit al Maqdis and hence with the ISIS. The same could happen in the Gaza Strip where a pro-ISIS brigade named after Sheykh Abu al Nur al Maqdisi has appeared. A bonding of the Palestinian cause with that of the ISIS would be realistically dangerous. And if we move further west, the same could happen in the Polisario camps in Tindouf, where the frustrations deriving from a lack of any progress on the issue of Western Sahara has increased the support for the ISIS. The ISIS will thus become a global threat if these ties become real. Time is on their part. The longer they will be left to consolidate their State, the lesser they will appear as a transitory phenomena. As recently stated by Saudi Arabia’s longtime and now former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Saud bin Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, it will take a decade to uproot Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s organization. But this prevision does not contemplate the threat coming from the bonding of the different groups now scattered around the globe.