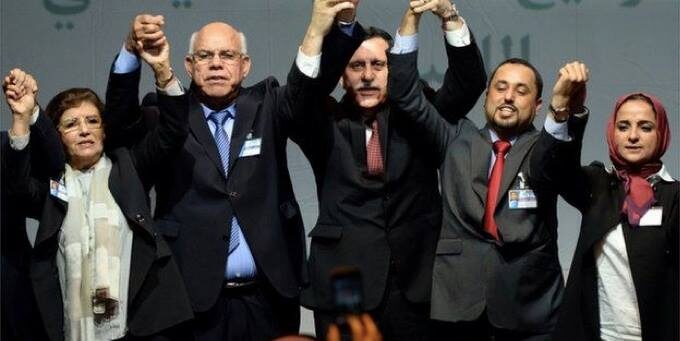

DIRTY GAME IN LIBYA

Lybian leaders after signing the Skhirat agreement

On December 17, 2015, in Skhirat, Morocco, a peace deal was signed to pacify Libya. It was hailed by UN’s representative, Martin Kobler, and other politicians as a “historical day for Libya” and “the beginning of a long road to peace”. Several signatories attended the ceremony: 80 out 188 MPs from the Parliament in Tobruk, 50 out of 136 of parliamentarians from Tripoli. The agreement was the result of lengthy negotiations abroad which had overcome a series of obstacles. The two governments in Tripoli and Tobruk did not share the same vision as to how to solve the Libyan stand-off. A number of international mediators had to intervene: Arab countries, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon. The United Nations and the Security Council blessed the signature of the deal and promised to support the Libyan military in the fight against terrorism, lift the arms embargo once a government of national unity was formed and aid other key sectors.

Two years on, nothing has been done to reunify the country. Euphoria has been replaced by frustration. In addition to the two governments ruling over the country, the international community has sponsored a third. The Government of National Accord led by PM Fayez Mustafa al Sarraj co-exists with the ones in Tripoli and Tobruk. And since March 30, 2016 al Sarraj is confined to the Abu Sitta naval base after a coup attempt tried to oust him. The internationally sponsored government is now without any political, economic or military power. Even the Libyan Central Bank and the National Oil Company have taken a step back after their initial support to al Sarraj. And without resources, oil or an army, failure is just around the corner. Meanwhile, Libya’s security deteriorates.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon in Tripoli

Shared responsibilities Are the Libyans to blame? Definitely yes. Five years on, the civil war and the internal strife have led the country to collapse. The social texture of Libyan tribal and beduin society has fallen apart. The Kabyles, or tribes, through which Muammar Khadafi used to control power and territory, have lost their influence. Armed militias have taken over and they have their own agenda. Weapons talk more than traditional assemblies. The economy has also collapsed. There is no difference between legal and illegal activities, trade or smuggling as several militias behave more like criminal gangs. The fact that they have have found a way to enrich themselves and that these sources of income could disappear if rule of law is re-established poses a huge challenge for the future of Libya. Is the UN to blame? The United Nations pays the price of its operational limits. They are very active when it comes to negotiating and extremely passive when deals have to be put into practice. They always lack the force to impose what was agreed upon. The UN’s mission in Libya, UNSMIL (United Nations Support Mission in Libya), is political and not military. A wagon-load of good intentions (restoration of public security and rule of law, promotion of national reconciliation, political dialogue and the electoral process, protection of human rights etc.), but no tools to implement them. In a country in the hands of armed factions such as Libya is, the UN’s goodwill will not go very far. This is because the negotiations in Skhirat were flawed because only the parties willing to talk in the first place ended up signing the agreement. As expected, those against the talks are now in the frontline to sabotage that peace process. Those most responsible for the ongoing crisis in Libya are the members of the UN Security Council. They all sponsored the peace deal, but then chose a local ally to side with. With the exception of China, who shows little or not strategic interest in the Middle East and North Africa, the remaining members of the Security Council favored their national agenda and undermined those same negotiations they initially had sponsored and supported.

Russian manoeuvrings

Russia is going all in on General Khalifa Haftar, the ruler of the Cyrenaica and the main opponent of the reconciliation efforts led by al Sarraj’s government. Haftar was received in Moscow in November – a month later, another opponent to the Skhirat deal, the Speaker of the Parliament in Tobruk, Aguila Saleh Issa, also received a warm welcome in Russia – he granted the Russian fleet the right to exercise in Libyan national waters and boarded the Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, hosted in Tobruk the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia, Valerj Gerasimov, and had a video-conference with the Russian Minister of Defense, Sergey Kuzhugetovich Shoigu. All of the above happened in broad daylight, in a show of open political support. Although Moscow has officially denied supplying weapons to Haftar, Aguila Saleh underlined that Russia is ready to support and train the “Libyan army”. And by “Libyan army” he meant the “National Libyan Army” led by Haftar. Russia’s policy in Libya is part of Vladimir Putin’s wider Middle East’s agenda. Haftar is now Libya’s strong man. During Khadafi’s days he went for military training in Moscow and could turn out to be a useful pawn in Putin’s strategy in the Mediterranean Sea. In Libya, military might dictates politics, and Khalifa Haftar is among the mightiest. And he could build on his strength with Russian support. After Tartous and Latakia in Syria, a Libyan regime in good terms with Moscow could allow the Russian fleet a foothold in another port in the Mediterranean. Furthermore, by siding with Haftar, Russia is now on the same side as Egyptian General Abdel Fattah al Sisi. Egypt supports Khalifa Haftar against the Islamic militias that are active in Eastern Libya, along the Egyptian border. Cairo’s supplies of weapons and support is a waiver of UN sanctions.

Can Russia sponsor the talks in Skhirat and then side with the biggest opponent to the government of national unity? Vladimir Putin has never put ethics nor fair play at the top of his political action, especially now that he’s gained such a prominent role on the Middle Eastern chessboard. Putin’s rise is directly proportional to the US’s retreat from the region. The election of Donald Trump could favor a rapprochement with Moscow. And from what the President-elect has said in his first foreign policy statements, Libya appears nowhere close to the top of his list of priorities. According to Trump, this is a European problem. And if this approach is confirmed, Russia would definitely end up playing a lead role in the future of Libya.

Khalifa Haftar

The other players Russia isn’t the sole actor playing dirty in Libya. France has deployed its special forces in the Benina airport in Benghazi and, although not blatantly, supports Khalifa Haftar. The Brits do the same: they sponsored Skhirat and now side with the General. Both countries target Libyan oil, as 70% of Libya’s national production is concentrated in Cyrenaica, under Haftar’s control. He has even started using the oil terminals to sell gas and oil on his own. The US, at least while Barack Obama was still at the helm, has not played an intrusive role in Libya. They supported and carried out bombardments in favor of the Misrata militias in their fight against ISIS in Sirte, thus offering an indirect support to Fayez al Sarraj. In fact, the United States were probably the only members of the Security Council to advance the peace deal signed in Morocco. However, there were two drawbacks in the American intervention: the aerial missions – over 500 of them – targeted ISIS alone and were not a show of support for al Sarraj; any future initiatives will have to be decided by the new administration in Washington DC. The United States can withstand a politically correct attitude in Libya and can decide when and how to talk to Khalifa Haftar. After all, the Libyan General is a US citizen and was (and might well still be) on the CIA’s payroll for his role in fueling the uprising against Khadafi. He basically showed up out of nowhere in Libya in 2011, with a lot of money in his pockets and the likely approval and support of US intelligence. Trump’s lack of consideration for the United Nations could easily push the United States towards abandoning the UN-backed government of al Sarraj for Haftar. Other countries, instead of adhering to the international deal, have chosen to side with one of the Libyan factions. Qatar and Turkey both support the former Islamist Prime Minister Khalifa Ghwell in Tripoli. Ghwell tried twice to oust al Sarraj in October 2016 and January 2017. The UAE instead backs the government in Tobruk and its airplanes are deployed in an airbase in the Marji area, in Cyrenaica. Jordan has offered training to Khalifa Haftar’s officers. During the training sessions in Amman Haftar’s two sons, Saddam and Khalid, also joined in. The General’s children hold ranks in the military and, in the consolidated tradition of Arab regimes, already pose as the heirs of their father’s power. The country that has more openly supported al Sarraj is Italy. Officials statements, the deployment of a military hospital in Misrata during the attack on ISIS, the re-opening – a first among European countries – of the embassy in Tripoli and the signature of a cooperation and assistance deal with al Sarraj to fight against organized crime and illegal immigration are clear indications of Rome’s strategy. The Italian attitude has been met with opposition from those hostile to al Sarraj. Khalifa Ghwell has labeled the Italian moves as a form of “neocolonialism”. Haftar warned Italy to keep away from domestic Libyan affairs. However, Italy runs with the hare and hunts with the hound. Haftar has frequent and direct contacts with the heads of the AISE, the Italian intelligence agency tasked with external threats, as they keep their options open in case al Sarraj fails and the Libyan General takes over.

Outlook

It is now clear that Libya, a country that has no historical experience with democratic institutions, is having a hard time in implementing a national reconciliation agreement based on popular consensus. The main protagonists of the stand off share a similar attitude towards democracy. The “consensus” they seek will have to come through a show of force. The fact of the matter is that, among the three contenders, al Sarraj is the weakest from a military point of view. This implies that he is not receiving the international backing he was supposed to obtain. And this is ultimately due to the foul play by the international community, whose members have pursued national objectives to the detriment of peace in Libya. If a civil war breaks out, al Sarraj would be defeated twice. For one, the Misrata militias that support him are weaker than Haftar’s. They’ve lost three thousand men during the fight against ISIS in Sirte. Secondly, al Sarraj’s demise would mean the international peace process has failed in another blow to the UN’s conflict resolution “model”. A peaceful transition to democracy would be the next victim. Currently Khalifa Haftar can count on an “army” – a vaguely abusive term used to refer to a heterogeneous grouping of unqualified militants – of 30 thousand men, although he claims twice this figure. He’s also obtained the support of some Khadafi loyalists. When he asks Italy to stay out of the picture, Haftar is looking for enough room to act freely. The open or veiled support of Russia and Egypt exponentially increase his arrogance. The General’s air force has recently targeted an airport in the South of Libya were Misrata’s jets were stationing. This is the prodrome of a direct military confrontation between Haftar and his opponents. The strong man in Misrata is Fayed al Sarraj’s deputy, Ahmed Maitiq. He’s the only one who can possibly counter Haftar. Maitiq can count on an alleged force of 35 thousand men, split among 200 or so militias that fight for different reasons. Presently Libya is home to 200 thousand armed men and militants. The struggle between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, Haftar vs al Sarraj, is just one of many. As mentioned earlier, Khalifa Ghwell has tried twice to overthrow al Sarraj. Despite the failed coup attempts, he is still capable of roaming freely between Tripoli and Misrata. This shows the ultimate irrelevance of al Sarraj and the Government of National Accord.

A new Skhirat?

Diplomats have probably realized that the peace deal has failed and have begun a new round of talks. In October 2016 Paris hosted a conference on Libya and no representative from al Sarraj’s government was invited to attend. The UN is holding negotiations in Hammamet, while the US – that is until Trump steps in – seem willing to discuss the Libyan case. The African Union also met in Brazzaville, Congo, a few weeks ago. In front of delegates from the Arab League and the UN envoy Martin Kobler, Fayez al Sarraj asked that the sanctions be lifted. The meeting also underlined a necessary truth: a new political deal is needed, a new “compromise” must be found. The only way to prevent a bloodbath and a return to normal would be the signing of a deal between all three parties. If Russia were to put pressure on Tobruk, the US on al Sarraj and Turkey on Ghwell, a deal would be within reach in weeks. A new, internationally-backed government would be formed to include all parties. Fayed al Sarraj could maintain his political role, Khalifa Haftar oversee the reconstruction of the armed forces, and the militias would be gradually absorbed into the national army. Easier said than done. However, a fresh international attitude could convert a dirty game into a clean one. Without a deal the country is doomed for war, regardless of its outcome. Any conflict, with its string of the killings, can only bring more division. The civil war in Libya has caused over 1.500 victims in 2016. It was the same in 2015 and twice as much in 2014. More deaths will only make any national reconciliation a lot harder.