GAMBIA’S CASE, AN ORDINARY AFRICAN STORY

In a continent like Africa, the fact that Gambia’s President refuses to relinquish power after 22 years despite losing elections; that he is protected by the military; that he decides to leave the country only when Senegal’s troops begin to invade; that he finally chooses to escape to another country as a last resort, is no news. Unfortunately, Africa is plagued with dictatorships, poverty, aggrieved human rights and corruption. Yahya Jammeh, the former President of Gambia, is the rule, not the exception. In Africa, it is easier to remember the few existing democracies than the long list of corrupt regimes. Almost all African leaders take power through force or through elections that are more or less manipulated; more or less “democratic”. Inevitably, when their mandate expires, they refuse to relinquish the helm. Sometimes, when it is necessary to find a legitimate form to their claim to power, constitutions are changed. If the people disagree, the army and/or security services are ready to imprison or kill the opposition, and the insurrection is inevitably drowned in blood. But Gambia’s case is even more emblematic, well beyond fervid imagination.

Jammeh’s ousting

Jammeh lost the December 1st elections last year and immediately refused to step down. After all, he’d only been in power for 22 years. He soon began enacting the usual repression. The country risked being plunged amid a civil war? It wasn’t an ethical problem for Jammeh. In fact, his power was in the force of weapons, so if he couldn’t have consensus, he’d gladly have war. The army and his ‘Praetorians’ would legitimate his claim to power. Jammeh also had a clear design for the country’s future: he wanted to create an Islamic republic (he probably thought that giving religious connotations to the debate could create consensus); and he wanted to drop out of the Commonwealth (the UK was not in good terms with him). But Gambia is a small and poor country, completely encircled by its neighbor, Senegal. So the authorities in Dakar, who supported the winner of the elections, Adama Barrow (who fled to Senegal in order to save his life), told Jammeh that he had to step down. Adama Barrow had already been assigned as President in Dakar, seen that he could not go to Banjul for fear of being killed by Jammeh.

Convincing Jammeh was no easy task. He tried to resist with the military at his side, but was forced to bow when faced with Senegal’s army. Jammeh’s 1000 men, plus a few African mercenaries, were no match for the 19000 men of the cumbersome neighbor.

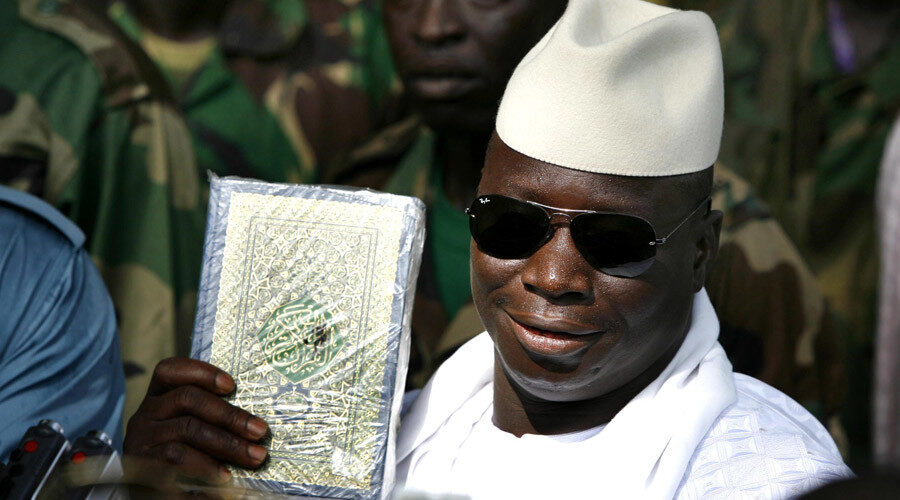

Yahya Jammeh

The mediation But in Africa, even when faced with blatant abuses of power on the part of autocratic and corrupt individuals – although Jammah was just a small fish compared to other dictators – people try to mediate. The corrupt dictator doesn’t get the boot, instead, there are negotiations, attempts to find a painless solution, especially with regards to the ousted satrap. The mediator in this case was Guinea-Conakry’s Alpha Condè, who is one of the few legitimate presidents in Africa. He won the elections in 2010 after a long dictatorship, he underwent an attempt on his life during a failed coup and came back to win the elections again in 2015. He was accused of manipulating the electoral results, but in Africa it is a venial sin. Actually, it is not even a sin but a mere habit. Condè was the mediator because Guinea is one of the most important countries (after Senegal) in Western Africa. Did he do it for humanitarian reasons? Or maybe to avoid the latest social catastrophe? Maybe for both. Either way, he mediated. Another mediator was Mauritania’s President/General Ould Abdel Aziz. Aziz is somewhat of an expert in coup d’etats. He participated in his first coup in 2015 when he supported Sidi Mohammed Ould Cheych Adballahi against a preceding dictator. Then the relationship between the two turned sour. But in August 2008, Aziz had his very own coup. After all, in Mauritania, power is historically passed on from one coup to the next. Shortly after the coup, Abdel Aziz received the dissent of the African Union, which didn’t seem to appreciate turbulent changes in power, but he soon found a powerful ally in Gheddafi, who was rotating president of the AU at the time. With the blessing and complacency of the Libyan dictator, the Mauritanian dictator was rehabilitated. Perhaps that’s why he wanted to spend his efforts in the mediation for his Gambian colleague Jammeh. But these were not the only mediators. Everyone in Western Africa seemed to feel the need to find a peaceful solution to the Gambian problem, even ECOWAS (the Economic Comminity of Western Africa, whose members are the 15 countries in that region). But even they didn’t ask Jammeh to just get up and leave. Instead, they proposed bargains to convince him; they offered to find an ‘honorable’ exit strategy for him without harming the country. He had to leave, of course, but he could come back to the country without any restriction if he wished. He could, if only he wanted to, run as a candidate in the next presidential election. ECOWAS guaranteed, as did the African Union, and in a way the UN, which supports the ECOWAS’ political initiatives with a resolution.

Jammeh’s guarantees

At that point, Jammeh was appeased by such guarantees, but still skeptical. His real guarantee was the money that he would take with him. He began by cleaning out the country’s safes of about 11 million dollars in local currency, gold and foreign currency. It’s a small sum of money, but Gambia is a very poor country and there was nothing left to steal. It was enough, however, to create the basis for the country’s bankruptcy, but that didn’t bother Jammah. What really bothered him was the volume of the stuff that he wanted to take with him. He would be needing a special transport for it. So there came along the President of Chad, Idriss Deby, who sent a special cargo plane so that Jammeh could load his personal provisions on it. Deby reached power in Chad in 1990 by toppling another dictator, Hissene Habré. Habré was a tough cookie; he was even condemned for crimes against humanity. So is Deby a dictator? No, because he wins the presidential elections every 5 years. Granted, in his country corruption is rampant and there is a system of political patronage to find work in the public sector that fuels further corruption. Every now and then Deby launches campaigns against corruption (which strike at the opposition, not at his friends). His human rights record is not the cleanest around, but Deby is supported by the French and the US; he has a gift for snuggling himself into other African crises (Chad fights alongside the French in Mali against Islamic terrorists, they help the Central African Republic against the rebels, they fight Boko Haram by providing troops to the African Union). After all, Idriss Deby is useful and his abuses are easily forgiven. So Deby sent the cargo plane and Jammeh jumped at the opportunity. He didn’t just carry money, jewels, gold and all that is needed for a golden exile on the airplane; he also loaded luxury cars (the limited room on the airplane did not allow him to carry all of them) and the presidential palace’s furniture, including the statues. All of the things that could remind him of the splendor of the days past.

As Chad provided the airplane to carry the loot, Alpha Condè sent another airplane to escort the exiled dictator out of Gambia.

Where to find refuge? At this point it would be fair to ask oneself where an individual like Jammeh could find hospitality. After all, he could be indicted by any international court at any given time. But in Africa, the opportunities offered to individuals such as the former Gambian president are endless. The hospitality, or better, the political exile, was readily offered by the President of Equatorial Guinea, who is notoriously one of the continent’s most ruthless dictators. Obiang has ruled Equatorial Guinea since August 1979. He took power in a rather grisly military coup against President Macias Nguema, his uncle, who was later sentenced to death and executed. Macias himself was no boy-scout. He had carried out his own mass executions and indiscriminate massacres. In his time, Equatorial Guinea was called the Dachau of Africa. After all, the rise of Obiang and the killing of Macias were positive turns for the country. Unfortunately for Guineans, under his uncle’s rule, Obiang had experienced the violation of human rights as he served as head of Black Beach prison, where torture and murder were the routine, and the teachings had stuck. Obiang had either been consensual or acquiescent with his uncle’s violence, that’s for sure. Now that Omar Bongo from Gabon (the bordering country) and Gheddafi from Libya are dead, Obiang is the longest-lasting dictator on the continent. Second best goes to the President of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, who is in power since 1987. But Obiang breaks yet another record, apart from those of Royal descent, he is the world’s longest-lasting president. If one were to ask him how a president can stay in office that long, Obiang would probably say that one just needs to obtain popular consensus from time to time, in whatever way, peaceful or violent. Every 7 years Obiang’s presidential mandate is reconfirmed. He is voted by no less than 93% of voters in any election. Although there is a multi-party system in place since 1992 in Equatorial Guinea, when Obiang runs for elections, nobody from the opposition feels the need to do the same. Of course, the security forces of Equatorial Guinea are renown for extra-judicial executions, kidnappings, torture and arbitrary detention. But these are just irrelevant details. Sometimes – it is said – the President presides the tortures in person. In short, Obiang is a megalomaniac who thinks he is a deity with supernatural powers. He likes to be called “boss” and at times likes to use the power of witchcraft against his enemies. Despite his penchant for the paranormal, Obiang exercises absolute power over what goes on in his country and over the lives of its inhabitants. And giving refuge to Jammeh won’t create a case of conscience for Obiang. After all, the two have similar ideals and conducts. Obiang is the luckier of the two because his country is rich in oil. He has accumulated such wealth that Jammeh’s 11 millions look ridiculous in comparison. Obiang passed a decree so that the money of the nation of Equatorial Guinea would be transferred to an account in his and his family’s name. There exists no difference between his money and that of the State; he IS the State. Unsurprisingly, his son has been recently placed on trial in France for corruption and theft of public funds and the USA and Spain are investigating Obiang and his son for the same crimes. The wealth of petrol allowed Obiang’s regime to cruise unscathed past the accusations of human rights violations that are raised cyclically internationally. He has the protection of Spain (of which EG was a colony), the acquiescence of the US and the guilty negligence of many other nations. Even the Pope received Obiang in grand style in 2013.

A quiet future for Jammeh

By moving to Equatorial Guinea, Yahya Jammeh has won a quiet and peaceful future for himself. He’s 52, with a quite long life expectancy, during which life he can count on the stability of the Guinean regime. Obiang is 75 years old but, as per dictatorial tradition, his power will be passed on to his children. By the way, if ever an international court should decide to put the former Gambia President on the stand for his crimes, Guinea provides a simple solution: it has not accepted the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Jammeh can be severely criticized for his thieving habits, for his scarce sense of democracy and for his even scarcer sensibility for human rights, but one must admit that settling in Equatorial Guinea was a good move. Nigeria was also willing to give him asylum, but Jammeh had better vibes about Malabo. Any regrets left in Banjul? Yes, having to abandon the army that supported him and that fled at the site of the new president and of Senegal’s troops. Even the Liberian and Ivory Coast mercenaries turned and scuttled away. Unfortunately for the continent and its future perspectives, the story of Yahya Jammeh is not the exception that proves the rule, but the rule itself. Is it part of the inheritance of a colonialism that taught no ethical or democratic values to the subjugated populations? Maybe in the past. Today Africa should accept responsibility for and learn to fight its inner social injustice and authoritarian abuses. In addition, Africa should also learn to pursue legality and frown on theft, illegal wealth and corruption. Examples like that of Yahya Jammeh are not helping the cause.