THE MIDDLE EAST CHANGES, BUT FOREIGN POLICY DOES NOT FOLLOW

The Arab Spring has forced several countries to face an arab world in turmoil, where old alliances and rivalries have been modified by events. All those countries whose foreign policy had been crystallized between friends and foes have been forced to modify their attitude. They had to change their approach and decide, on the wave of social pressure, which horse to bet on, whether to support new leaderships or to refuse them and whether to opt for the benefits of a revolution or to settle for the comfort of restoration. All those alliances and rivalries sedimented over time suddenly crumbled and all foreign policy decision-makers were faced with unexpected choices, maybe painful one, sometimes opportunistic and definitely based more on the emotion of events rather than rationality.

We are all brothers

The Muslim Brotherhood takes over in Egypt? The United States opt to support the liberal and democratic wave across the country. They do so despite the decades long alliance between Washington and the military elite in Cairo. They abandon an isolated, sick and exhausted Hosni Mubarak to his destiny. And, without the necessary question marks such an issue would have required, the U.S. side with the Brotherhood, regardless of their traditional hostility to the American presence in the the region and to the existence of Israel, Washington’s historical ally.

Saudi Arabia faces the same problem. The Saudi regime finds itself in the uncomfortable position of having to accept an islamic leadership under the guidance of a group, the Muslim Brotherhood, that is not particularly appreciated by the followers of Wahabism and despite the traditional support the Saudi reign has granted to the Egyptian military. But, with respect to the United States, the Saudis do not open handedly embrace the new Egyptian leadership. They keep themselves at the margin of a formal relationship. Saudi Arabia does not like revolutions and especially those revolts tainted with religious motivations and lead by politicized Islam. In other words: they don’t like the Muslim Brotherhood.

Instead, the Brotherhood’s takeover is greeted with cheers by Ankara. The events in Cairo resemble those in Turkey: a military elite has been replaced by an islamic party. Mohamed Morsi is perceived as Egypt’s Recep Erdogan. The Egyptian Justice and Freedom Party as the Turkish AKP.

It is then for Qatar, a small country with great ambitions. The fall of the Egyptian regime provides Doha with the room to play its own ruthless foreign policy. And the reason is not the alleged affinity between the Brotherhood and the emirate. It is rather the creeping competition with the Saudis. Ryad fears all those radical islamic organizations proliferating in the Middle East? This is not an issue for Qatar. It actually offers unchartered territories to develop and consolidate a series of Islamic flavored options in support to everything, both new and old, that is not appreciated by the Saudis.

The North-African springs

The events in Tunisia pose the same sort of issues: a military regime, a revolution, an islamic party taking over. The United States have once again the same attitude and immediately embrace the alleged wailing of a nascent Tunisian democracy (without thinking too much about the lack of affinity between the U.S. and Rachid Ghannouchi’s Salafi Islam). On the other hand, the Saudis hesitate, while Turks and Qatar rejoice. Ryad goes a step further: they offer refuge to Ben Ali.

Rachid Ghannouchi, the exiled Tunisian leader whom for decades had been looked upon with suspicion by the West for the alleged ties between his Ennahda movement and islamic terrorism, suddenly turns into the icon of an arab world seeking social justice, democracy and freedom. No one pays any marginal attention to his troubled past. Ben Ali was a convenient dictator for many. Now he is not an autocrat despised by the international community for, together with the Trabelsi family, the systematic embezzlement of the State funds and for human rights violations.

And we now come to Libya. Muammar Geddafi was not loved by the West, nor by the arabs. An international military intervention is necessary to oust him. Qatar first pledges and then contributes to the military operations. Saudi Arabia keeps a neutral stance. The United States are pulled in by French activism and concur to the final victory on the ground. Turkey, initially against the intervention because of its good relationship with Geddafi, moves to a neutral position. Algeria is also against the attack fearing – rightfully – that the defenestration of the Rais will lead to instability and offer room to islamic terrorism.

Algiers does not look favorably upon Hosni Mubarak’s fall in Cairo, nor Ben Ali’s demise in Tunis. Algeria has always been ruled by the military, even though through a third person like current president Abdelaziz Bouteflika. Algiers has always had a higher degree of empathy for those leaderships more similar to theirs. And it has constantly adversed any radical islamic faction and terrorism. After all, Algeria has been fighting internal terrorism for over 20 years, thousands of people have been killed and it fears there could be a further contagion from countries with which it had started anti-terrorism cooperation.

From Syria to Palestine

Then Syria comes into the picture. This is not really an issue for the United States: the Alawite regime has always been an enemy for its stance against Israel and its traditional relationship with the Soviet Union yesterday and with Russia today. The issue facing the U.S. is, on a political level, the Russian support to Bashar al Assad (that has prevented any decision being taken at the U.N. and blocked any diplomatic option to get rid of the Syrian dictator) and, on practical terms, how to help the rebellion trying to overthrow the regime. Washington has encountered a series of difficulties in identifying a credible leadership capable of uniting the rebels. They also have still not decided which types weapons and to whom they should be handed out to. There is the reasonable fear they could fall in the wrong hands.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar face the very same issues. They both politically support the rebellion. But Ryad fears the weapons could be supplied to radical islamic groups and that these, once the war is over, could return home and affect the reign’s stability. In fact, there are way too many Saudis among the islamic “volunteers”. And many of them receive funding (and thus the possibility of purchasing weapons) from Saudi wahabi charitable organizations. Thus, Syria is for Ryad both a foreign policy issue and a national security one.

Qatar’s ruthless behavior allows the gulf state to provide weapons to the rebels regardless of their potential dangerousness. If, as is probable, the Alawite regime were to be replaced by its most credible opposition – the Muslim Brotherhood in this case – Doha has a lot to gain from this change. This is also because, in the course of the different arab springs, Qatar has always taken the sides of the Brotherhood and of all other islamic movements or parties. As opposed to Ryad, Doha’s foreign policy is not affected by the Sunni-Shiite competition. It does not host a Shiite community on its territory, does not have any pending issues with Iran and is not linked, as opposed to the Saudis, to the politics of religion.

Positions spread apart also with regard to Palestine. Mohamed Morsi’s Egypt had immediately found consonance with Hamas’ policies. It couldn’t have been otherwise given that Khaled Mashal’s movement was a political and religious offspring of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. The same was for Qatar: it sided with the movement based in Gaza. Saudi Arabia instead decided to support the PLO. The United States were, once again, floored. They supported Morsi, but were in great difficulty with Mashal’s extremism and intemperance. Washington decided to “wait and see” and allowed the words of diplomacy to take the floor: we want peace between Israelis and Palestinians, we hope Mohamed Morsi’s influence will lead Hamas to moderate and negotiating terms and we condemn all forms of violence.

A change of situation

This was basically the picture of how foreign policy relationships changed following the Arab springs. A capsizing of ties, alliances and connivances crystallized over time. A series of hard choices, often against nature, but definitely necessary to limit the damages that the new context could have caused to individual national interests.

The assumption was always the same one: people want democracy and social justice, the arab springs represent a yearning for freedom in a region for too long dominated by abuses and prevarications. It is hence right to ride these aspirations. But things were not as clear-cut as they seemed: behind the social upheavals there wasn’t only the yearning for democracy, but also requests for social compensation, dire economic conditions and desire for revenge.

So different from what had been imagined, the truth revealed itself for what it really was: when a regime fell social anarchy took over (Libya), once a military dictatorship was chased out pseudo-democracies replaced it together with their Islamic and regressive interpretation of social freedoms (Egypt and Tunisia), the battles for democratic revolutions turned into magnets for jihadists from all over (Syria). There are a few common elements: chaos, deaths, protests, growth of islamic terrorism. Attacks in Libya, attacks in Syria, attacks in Turkey, Egypt and Tunisia on the brink of civil war.

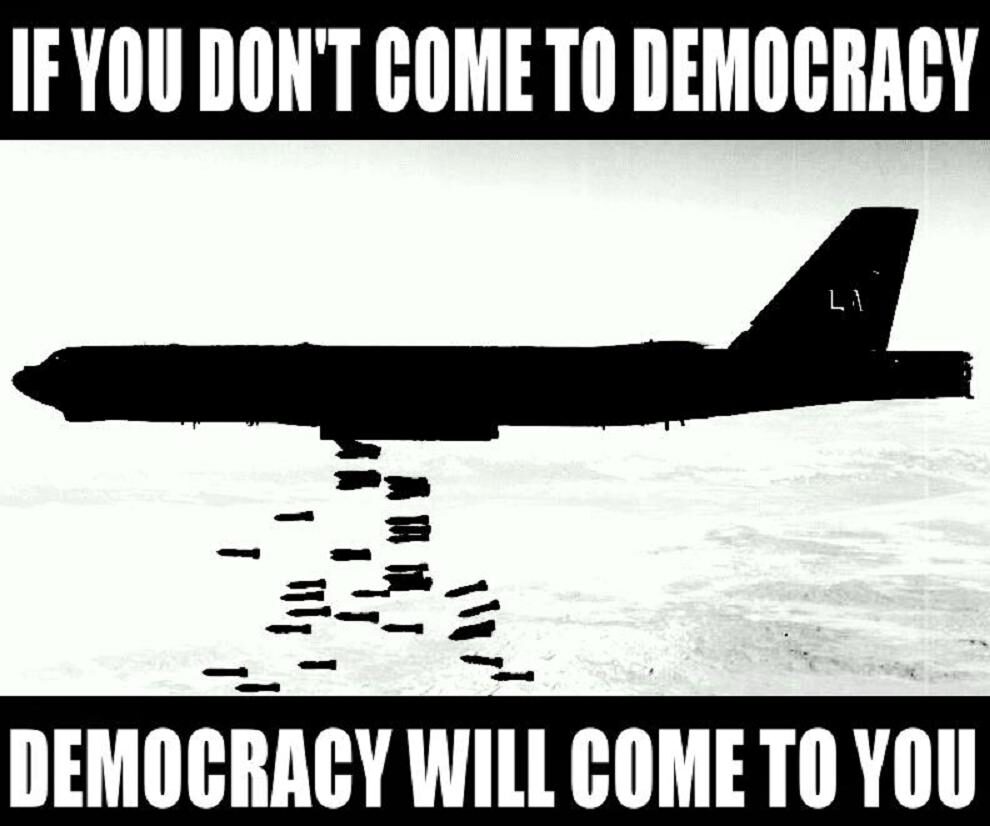

No exportation of democracy, a phrase dear to the hardly mourned U.S. president George W. Bush. The actors of each national drama changed, but their methods of handling power remained the same. There was then one last evolution: restoration. The first to start were the Egyptians on June 30 2013 with the arrest of president elect Mohamed Morsi. In Tunisia the Islamist-lead democracy is in crisis with way too many opposition deaths in search of an author. In Syria, Bashar al Assad’s regime has not fallen, but is now militarily regaining ground.

Historical twists and turns overlap. Everything changes, but, in the end, nothing really does. The issue is now how all those countries that supported the Arab Springs are going to reposition themselves. The United States initially supported Hosni Mubarak and his military elite, they then immediately converted to Mohamed Morsi’s ideas and now that General Abdel Fattah al Sissi has taken over what are they going to do? Will they go from supporting the revolution to siding with restoration in a dramatic foreign policy u-turn?

Will Washington support the Tunisian islamic leadership that has proven incapable of answering to the people’s demands, while allowing extremist salafist groups to proliferate and physically eliminate opponents?

If Bashar al Assad’s regime does not fall, but strengthens its position, will it be better to favor the dialogue with Russia or is it really worth supporting a rebellion that has gradually fallen in the hands of groups linked with Al Qaeda?

The issue of where to stand in an arab and islamic world in continuous social turmoil and that easily confounds the spring of ideas with the autumn of reality concerns not only the United States. With Morsi in jail Qatar’s choices are also penalized, as is Erdogan’s imaginary hardly hit, while there are new chances for Ryad’s foreign policy.

While in Tunisia protesters take the streets, does the U.S. have time to rethink its position, for Qatar to withdraw its support to Ennahda or did Saudi prudence prove right once again?

These are all questions that have still not found adequate replies. But one thing is for certain: events within each country now set the agenda of foreign policy decision-makers and not vice-versa. Events anticipate and determine intentions. And after decades of sclerotic immobility, foreign policy in the Middle East – both for the countries in the region and for the West – has a hard time understanding and adapting to a mutating world whose future is still difficult to predict. We are witnessing a series of national stories still without an ending, but, above all, on whose final outcome external actors’ foreign policy will have little or no impact.