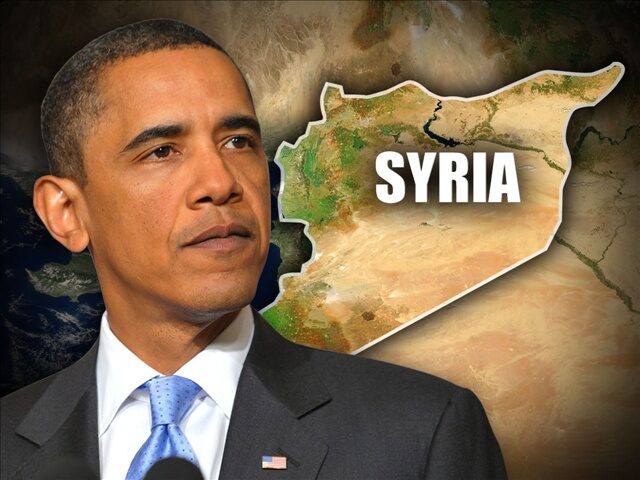

UNITED STATE’S SYRIA ENIGMA

U.S. President Barack Obama had traced a “red line” forbidding the use of chemical weapons by the regime in Syria in the fight against the rebellion. After several denials, tests, journalistic investigations and international pressure, that “red line” seems to have been crossed.

The direct consequence of such a circumstance should have been a U.S. intervention against Damascus. But the Obama Administration’s first moves show a prudent behavior on what to do next to help the rebels in their fight against Bashar al Assad’s loyalists.

If, for technical reasons, the imposition of a no-fly zone over the north of Syria has been ruled out, there are only two operational options left on the table: the supply of weapons to the rebels and/or a direct support in the form of foreign troops fighting alongside the rebellion. Imposing a no-fly zone would imply the prior destruction of Syria’s aerial defense system; not doing so would endanger the flights of the forces employed in the enforcement of the aerial blockade. This would require an initial bombardment of radar and missile posts utilized for defense purposes and an attack against the enemy’s command and control system. On the other hand, a direct support to the rebels and their flanking on the ground would also require a direct U.S. intervention, but that would also increase the dangers associated with the operation. An armed intervention also postulates the coming into play of other countries (and there are none available on the market at the moment). Hence, whether the U.S. likes it or not, there is only one option left: arm the rebels.

The U.S. reluctance against a direct involvement against the Bashar al Assad’s regime is not dictated by Russia’s opposition to external military interventions in Syria’s internal affairs, but rather by the United States’ foreign policy decisions. A military intervention would contradict President Barack Obama’s policy of pulling out of theaters of operation such as Iraq and Afghanistan where costs and difficulties have outweighed gains. At the same time, an armed action could determine a final outcome – as has happened in Libya – contrary to U.S. interests.

Reluctance has thus turned into prudence and prudence into ludicrous measures.

Firstly, great difficulties have emerged in supplying weapons to the rebels because not all the groups fighting against Bashar al Assad are considered “reliable” and thus qualified for receiving U.S. support. As a matter of fact, there are groups such as Jabath al Nusra that are linked to Al Qaeda, there are highly dangerous extremist factions and Washington needs to assess who should receive the weapons and who should not. This is not an easy task given the varied articulations of the rebel forces that make each choice a difficult one. Furthermore, there is no assurance that the weapons supplied to a “reliable” group will not fall in the hands of an “unreliable” one. The United States still remembers what happened in Afghanistan when the Stinger missiles handed over to the Mujahedin to fight against the Soviets ended up in terrorist hands.

The second issue is what kind of weapons should be supplied to the rebels: should they be given efficient, mainly anti-aircraft systems as required by their theater of operations or should the supply be a mere facade and nothing more than a political gesture? It is pretty evident that if the United States are not sure where these weapons will end up, they will tend to reduce the supplies to the minimum. In a context already abundant with weapons such as the Middle East, fostering the market even further could create more problems.

There is still another issue that needs to be solved: both the Alawite regime and the rebels use weapons coming from former Warsaw Pact countries (now Eastern Europe) and Russia (former Soviet Union). This implies that any logistical supply will have to take this factor into consideration (also because weapons seized from loyalists could be used against them) and it would make sense to continue supplying rebels with weapons coming from that part of the world. This would mean that the United States will have to purchase weapons supplies on the free market and thus collide, not only politically, with Russia.

Lastly, U.S. policy decisions will also have to overcome a last obstacle: Turkey. Ankara has refused to allow weapons destined to rebels to go through its territory. This is a decision Turkish PM Recep Tayyip Erdogan has communicated by phone to President Barack Obama on June 19 2013. Why did Turkey, after having hosted for the Syrian opposition and its military command for a long time, have such an unexpected change of position? There are a series of reasons and they are all correlated.

Firstly, Turkey has become the target of attacks – like the one on May 11 2013 in Reyhanli that has killed 53 people – and this denotes the export of the Syrian instability within its boundaries. The transit of weapons to the rebels and the flow of armed groups to and from Syria will definitely not improve the security of the country. Internal issues related to the arrogance of Erdogan and of his Islamic party’s policies have also added up to the regional instability. The diatribe between the Turkish PM and the West was ignited by the criticism over how the Turkish government has handled protests, the same happened with the police and its brutal methods. Turkish authorities have thus parted ways with those countries supporting the Syrian rebellion.

Recep Erdogan has felt betrayed and abandoned and, once again, has re-directed his foreign policy towards Neo-Ottoman stances: a greater distance from Europe and its obsessive request for human rights protection, greater attention to Arab and regional issues, pursue of an equidistant policy from NATO. After all, the spark that lead to the protests was borne out of the intention of the ruling AKP party to introduce Islamic precepts in a widely westernized and secular society. Parting ways with the West is thus the signal of a religious biased diversity.

The Turkish PM is also worried of what is happening inside Syria. The loyalists’ reconquest of the city of Qusayr certifies that the Bashar al Assad’s regime is far from military collapse. The nemesis of the Syrian rebellion still lacks an unavoidable ending. With the opening of negotiations in Geneva, it is wiser and more prudent for Turkey to keep a low profile with regard to Syrian affairs. Furthermore, this is not Recep Erdogan’s first denial to the United States. Even in 2003 he had turned down a U.S. request of opening a war front in the north of Iraq.

Whatever the political or practical motives behind the Turkish attitude, Washington faces another problem: how to bring weapons to the rebels. If Lebanon and Iraq are excluded for practical reasons, Israel for political motives, the only option left to deliver weapons to the Syrians is through Jordan. In fact, this is where U.S. efforts are focusing. Nonetheless, an arms influx through the south of Syria will penalize the supply to the northern front of the rebellion that, after the fall of Qusayr, is cut off from the supplies coming from the Lebanese Sunnis. When, in the near future, the fight will be for the supremacy over Aleppo and surroundings (where Hezbollah units, Shiite Iraqi militias and Iranian Basijis are already concentrating), weapons’ supplies from the south will pose serious procurement problems to the rebels.

Furthermore, Jordan poses a series of logistical issues. It can only rely on one commercial harbor in Aqaba (if compared to several Turkish ports). It does not have on its territory NATO air bases or NATO logistical infrastructure (as opposed to Turkey). So it is by far less functional not only for the direct supply to Syria, but also for the influx of weapons from abroad. King Abdallah rules over a country under the Western sphere of influence. His country – lacking any resources of its own – depends on systematic international aid and serving U.S. strategic interests can be taken for granted and is more than welcome (because it means there will be more benefice in the future).

It is not by chance that Jordan has been hosting Syrian rebels training camps with U.S. instructors. The United States, probably more out of a symbolic gesture than out of resolve, has sent 700 troops to Jordan in addition to the 300 men that have been sojourning in the Hashemite kingdom since last year. This was done in conjunction with the yearly military drills held in Amman and that were suspended because of the ongoing conflict in Syria. Besides from the ground troops, Jordan is now hosting two batteries of Patriot missiles together with its crews and logistical support and around 20 F-16 fighter jets that landed for the drills and that were never repatriated in the United States.

Overall, the U.S. military initiatives have a greater defensive value rather than an offensive one. And if one were to evaluate their impact, they indicate that the United States have no intention of directly intervening on Syrian soil. Rather than a menace against the Alawite regime, they represent for Damascus the confirmation that they can operate with resolve against the rebels, possibly dosing with precaution the use of chemical weapons, and nothing more.

In the midst of the diatribe over whether to intervene or not in Syria there is also the issue of the S-300 missiles Russia wants to hand over to the authorities in Damascus. In a public statement on June 20 2013, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has confirmed Moscow’s green light to the supply. This is another signal that the Russians will not let the United States move free handedly on the Middle Eastern chessboard.

Directly or indirectly, the Syrian issue has turned into a high value strategic game. A war of nerves – interspersed by menaces and offers for dialogue and mediation – in the attempt of ruling over the Middle East, whose strategic importance shall be retained as long as its oil resources are considered essential. And if the menaces lack the fundamentalists to make them credible, then room is left for talks in the apparent objective of seeking a negotiated solution to the crisis.

Bashar al Assad

“Geneva 1” started out in June 2012 when a group in support of Syria (composed by UN Security Council members and regional representatives) formulated the hypothesis of creating a transitional government in the country. We are now at “Geneva 2” (a conference still lacking a debut date) and at the informal talks that were held during the G-8 summit in Northern Ireland in June 2013. But the greater the space allowed for negotiations to start, even though probably inconclusive and rhetoric, the lesser the chances of feeling the need of a direct involvement in Syrian affairs by the United States and other international actors.

This is probably why the internal debate in the U.S. over to who, what and how to supply weapons to the rebels is filled with semantic blabber serving a vague empirical diplomatic approach whose only purpose is to conceal Barack Obama’s reluctance to intervening in Syria. The terms of the negotiations are the same as they were yesterday: the effort to put an end to the civil war, the creation of a transitional government, the 1.5 billion dollars pledge in humanitarian aid, the obligation for those participating in the negotiations to respect the agreements, the will to chase out of Syria both terrorists and extremists, a strong condemnation against the use of chemical weapons.

In the mean time, Bashar al Assad is still holding on to power, the atrocities of the war continue, “terrorists” and “extremists” (even though it is unclear on which side they fight on) continue roaming around, and the chemical weapons – that all sides deny having used – will probably soon resurface on the ground.