IS THE ISIS REALLY DEFEATED?

The military defeats of the ISIS must have induced many to think that Islamic terror like Al Baghdadi’s ISIS or Al Qaeda was alas nearing extinction. But reality is another cup of tea: although the idea of setting up a caliphate in the Arab regions of the world waned with each defeat, radical Islamic ideology is very much alive. The ambitious theocratic design that impressed many Islamic volunteers around the globe was downsized but the goals of the Salafi doctrine that inspired the ISIS will not be abandoned. There was a shift from conventional warfare to a non-conventional kind of fight called terrorism. And the warfare of terror does not feed on territorial conquest but on the charm of an ideology, on the just cause of a war fought for religion’s sake. In practical terms, the open war waged by the ISIS to conquer a territory was in ways less dangerous than crawling terror where each person can become a target; where all are afraid. Non-specific danger creates uncertainty and the enemy becomes invisible and unpredictable. Conventional warfare thus turns into a psychological confrontation. A more subtle and a harder one to fight. The ISIS is like the mythological Hydra, a monster whose heads reappear elsewhere each time they are chopped off. The ISIS was defeated in Syria and Iraq, losing almost all of the territory that it controlled. But the ISIS isn’t just about territory. It is about the ideas inherent in the radical Islam that accompanies it and it is currently seeking other theaters and other battles. Unfortunately, there are many around the globe.

The schools of thought

The Koran and the Sunna have always been the object of interpretation by the juridic schools of Islam, cultural gatherings where the dictates of Islam are transformed into laws. The approach of these schools loosely reflects the tendencies of the “umma”, or the Islamic community as a whole. There is the “Hanafite” juridic school, the most widespread of the lot, which gives ample room to customs but also to opportunity (it tends to be moderate, albeit bound to tradition). This school is also considered to be “liberal” and tolerant. There is the “Maliki” school, especially rooted in Morocco and North Africa. This school is also moderate. There is the “Shafi’i” school, which often resorts to analytic reasoning (and thus leaves room for human intelligence in the elaboration of the laws of Islam). There is the “Hambali” school, the most dangerous of them all, because it leaves no room for human thought, nor to an analytic approach but is based solely on the literal communication of the sacred scriptures. Saudi Wahabi Islam is a descendant of the Hambali school and so are the ISIS and Al Qaeda. The dangerousness of Wahabi Islam is not only theological in nature but also financial, because it has rivers of Saudi money driving it. On the opposite front we find, especially in Africa, other moderate Islamic groups:

There is Sufism, which integrates the cult of Saints and is influenced by the strong cultural animist African roots. For this reason Sufis are seen by Salafis as apostates. Sufi Islam also gives birth to many confraternities (Qadiryyah, Muridyah, Tijanyyah, etc.) whose members share a common spiritual life tied to the rules of Islam.

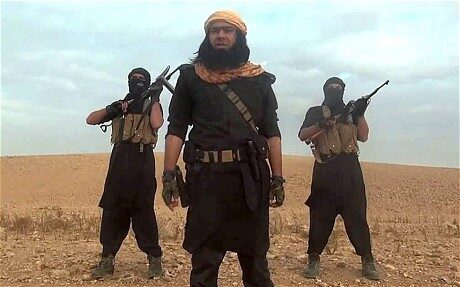

Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi

The cultural problem The ISIS feeds off symbols that justify its existence and produce followers and terror. Surely the ambition to set up their own State has been abandoned but there are other motivations that can give significance and justification to the terrorist’s fight. These ‘justifications’ are founded in religion, or rather in the radical interpretation of the sacred scriptures of Islam. The ISIS will not be uprooted by fighting it on the ground but rather on the Islamic, theological, level. The problem isn’t military – if not marginally so – but rather cultural. Once the religious premises that feed Islamic terror fail, the support that the ISIS received in the Arab world and among the Muslim international community will also falter. In practice, the fight against Islamic terror must be fought in the Islamic world. This is especially true of the ISIS that – unlike Al Qaeda – targets apostates: people that, although Muslim, neglect the dictates of Islam. The clash today is between moderate Islam, like the one promoted by qualified schools of thought such as that of the Al Azhar University of Cairo, and Salafi Islam, where the Koran’s concepts are absorbed in their literal form, decontextualized or interpreted, and turned into the wealth of leaders that aren’t culturally and theologically qualified.

The volunteers

There are thousands of Islamic volunteers that fought in the ranks of the ISIS. For many of them it was a one-way ticket. They have been identified by their nations’ authorities and have committed crimes that they will be made accountable for. They don’t know where to hide and are looking for other, unstable, areas of the world where they can continue their religious fight. The Middle East, Africa and Asia offer many opportunities to these individuals.

In the Middle East

The ISIS, unlike Al Qaeda, has promoted the fight against Shiites and there is a strong possibility that it will continue to do so in the clash between Iran and its Sunni neighbors. Many volunteers could join the fight. But there are also other battles that they could join – like the Palestinian cause – by joining the ranks of the more extremist organizations in the region, such as Hamas or the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. They could move to Yemen where there are territories controlled by Al Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula. They could go to the Sinai, where there are three ‘just’ causes: to fight Al Sisi’s military regime; to fight along the border with Israel; to support the Palestinians in Gaza. Many of these volunteers are experienced veterans that could join many other battles as well: the Kurdish fight against Ankara; the Iraqi Kurdish fight or the former Baath party fight against the Shiite authorities in Baghdad; the Sunni fight against the Alawites. Wherever there is a crisis or a crawling civil war, there will be an opportunity for their presence. Every pretext pays. Even if there were no chance of a religious war, the sheer presence of authoritarian regimes, which the Middle East is riddled with, could justify a new war, a guerrilla attack or an act of terror.

Afghanistan and surroundings

In Afghanistan Al Qaeda is still strong. But there are differences in the approaches of Al Qaeda and the ISIS, especially in terms of targets and operative procedures. While the ISIS tries to strike against the “tafkir” – Muslims who do not follow the precepts of Islam (this category includes the Shiites and the moderate Muslims), Al Qaeda’s fight is centered on the “kafir”, or the miscreants: individuals who do not believe in the Islamic God (specifically speaking, Americans and Christians).

Despite the diversities, the strenuous competition to market each one’s brand and the evident military defeat on the ground, an agreement between these two formations cannot be ruled out. Afghanistan’s instability is contagious, especially in neighboring Islamic former Soviet republics like Tajikistan (a militarily feeble and socially unstable nation), Turkmenistan (also weak and unstable) and in some measure Uzbekistan.

The African continent Although African Islam is less ‘theological’ than Middle Eastern Islam, the religious connotation here has also become the reason for many battles. And if the religious motives are not sufficient, there are many other reasons and social claims onto which a religious tag can be applied. Muslim African countries are comprised of huge, unstable territories with uncontrolled borders and endless deserted areas; these are all parameters that give the Islamic volunteers an ideal operative scenario. According to analysts, there has recently been an increase in the number of African countries that have suffered Islamic terrorist attacks and in the number of victims thereof. It is a scourge fueled by the chronically poor population, their scarce cultural level, unemployment, the lack of essential services, the violation of human rights and in the social marginalization coupled with abuses perpetrated by the many African authoritarian regimes. The social element is often prevalent over the religious one. Interestingly enough, unlike in the Middle East, terrorism in Africa does not use the internet to recruit or indoctrinate its would-be members.

How the new terror is structured

The military defeat and the loss of territory forced the ISIS to change its ways. They abandoned a hierarchical, pyramidal and centralized structure to a adopt a new, decentralized form. In practice, each terrorist group presently operates independently: it finds its targets, fights where and how it pleases, has its own operative plans, its own economic independence and its own recruitment system. Al Baghdadi is no longer at the helm: his statement in August this year was more of a reminder that he is still alive rather than that he is still leading the troops. A terrorist threat made up of many independent structures is very difficult to uproot on the operative level. Every victory is partial, never whole.

How to fight terrorism

The US approach is purely military, at least as far as the ISIS and Al Qaeda in the Middle East, Africa and Asia are concerned: air strikes; widespread deployment of drones; special operations. But this asymmetrical war has moved out of the Middle East and taken root elsewhere as well.

The Italian approach

The Italian approach is a more cultural one and is channeled through the most important Mosque in the boot-shaped peninsula. The Rome Mosque is the epicenter of Muslim presence in Italy. The Cultural Center of this Mosque, which is the backbone of Italian Islam, is now headed by an Italian-Moroccan Muslim director. He is connected to the Malaki branch of Islam. This person, who is also a former member of Italian parliament, replaced the Saudi ambassador as director of the center. Not only was the previous director a foreigner, but a Wahabi as well. Italy is trying to be rid of radical Islam – inspired and controlled from abroad – in order to support a more moderate, Italian, Islam. It is an attempt, still too recent to evaluate, to promote the emergence of an Italian branch of Islam that takes into account the social and cultural context of the country it inhabits. Theological considerations notwithstanding, it is a positive note on the security level. Imams will be observed and the places where they teach – often set up abusively here and there in Italy – will also undergo controls. Last but not least, Italians will understand what is being said if the sermons will be in Italian.