MACRON’S LIBYA AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

One wonders whether the July 25 meeting in France between president Serraj and general Haftar can effectively unlock the political-military situation in Libya. Surely, as in all other diplomatic initiatives, that of the new French president Macron can contribute to the national reconciliation in Libya. However, its hasty nature seems to answer to a logic that is different from the objective that was officially declared.

The problems of the French initiative

The first problem is the unilateralism of the diplomatic initiative, which should have received prior coordination from the UN (its new representative, Libyan national Ghassam Salamé, who is notoriously pro-French, was sent on the scene but ended up playing a subordinate role. In addition, Salamé had not yet visited Tripoli as an official envoy of the UN). More oordination among European nations would have also been helpful, especially in the case of Italy, seen the problem of illegal immigration from Libya to the Italian peninsula. These elements give rise to doubts that Macron’s initiative is actually aimed at fueling French ‘grandeur’ and the country’s interventionist policy in Africa. Macron was in the midst of a crisis with the French military establishment and needed to bring into the national spotlight an issue that would heighten French national pride internationally. The second problem is in the substance of the Paris accord. It supposedly puts an end to armed fighting (except for the fight against terror), dismantles armed militias and ferries the country to presidential and parliamentary elections within the coming Spring. These objectives would be hard to achieve even if the only two parties in the Libyan social chaos were Serraj and Haftar. But the country is filled with armed militias whose disarmament is highly unlikely, there is an Islamic government in Tripoli that has no intention of receding (they are tagged ‘terrorists’ by Haftar himself) and there is a harsh rivalry between the Misurata militias that back Serraj and those of Haftar’s so-called Libyan National Army. Despite the international support he receives, Serraj has little power over his people, while Haftar tends to divide the country. Also, to think of holding elections in the Spring of 2018 in a country that is slowly disintegrating is hazardous to say the least. Whoever will decide to run for elections in Libya will want to do so from a position of military strength rather than through popular consensus. Neither Libya’s nor Haftar’s histories are reassuring in this regard. The third problem is that France is playing its own, personal, game in Libya. The presence of French special forces in Benina poses a serious doubt on the impartial role that every negotiating broker should play. It is not a secret that France favors Haftar. Especially because the general is supported by Egypt, Saudi Arabia and UAE, which means a very positive outlook as far as arms sales are concerned (including arms for Haftar himself). In addition to all this, there is the oil of Cyrenaica. Russia likes Haftar (and it seems he promised them the use of his naval bases), as does the US. In this context, the French mediation seems to go in the opposite direction compared to the decisions of the UN Security Council, which recognize Serraj as the only legitimate representative of the Libyan people. In practice, the Paris meeting has legitimized the role of Haftar as (international) interlocutor of the Libyan crisis, despite his refusal of the UN resolutions. The French initiative also penalizes Italy, that has put much effort in legitimizing the national reconciliation government led by Serraj. Italy is now politically marginalized. The fact that Serraj made a stop in Rome after the Paris meeting, while Haftar flew back to Libya is quite indicative in this regard. In backing Serraj, Italy has invested politically and economically in his government of national reconciliation, especially in terms of future immigration policies.

Perhaps it was a mistake on Italy’s part not to have insisted on having an Italian national as the official negotiator of the crisis, as the UN Secretary General Guterres had suggested. The idea was scrapped because it was though inappropriate to have a negotiator from a former colonial power. Perhaps Italy was afraid of being sucked into the Libyan feuds; or to be put on the stand for its historical ties to Libya; or maybe they just thought that they would have more room to maneuver without having to abide to international limitations.

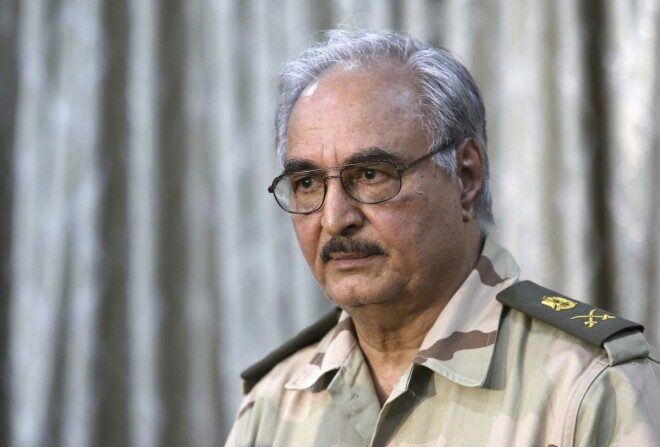

Il generale Khalifa Haftar

The reactions Notwithstanding, the French initiative triggered a number of reactions. Serraj, made strong by Italian support, asked the boot-shaped peninsula to help him fight illegal immigration in Libyan waters. He first sought help, then denied the request, then reconfirmed it. Serraj’s hesitation shows his utter political weakness. To have Italian warships cruising in Libya’s waters clearly undermines that country’s national sovereignty and gives Haftar and the Tobruk government good grounds for complaints. Haftar was backed in his complaints by another member of the Presidential Council, Fathi Majburi. Majburi is from Cyrenaica and thought it is wise to side with the strong man in Benghazi. Strangely enough, general Haftar saw no sovereignty problem in having UAE and Egyptian warplanes stationed and operational in Libyan territory. Feeling strong from the international backing he received, Haftar went so far as to threaten to bomb Italian ships that would dare enter Libyan waters. The fact that he has but a raggedy army made up of old Gheddafian supporters and a few, obsolete, Russian planes is not a problem because his intent is to create the cult of a ‘strong man’ who is fearless and invincible. In other words, he is trying to put his own feet in the dead Rais’ shoes, even in terms of the verbal fight against Italian colonialism. But the political significance of the above events is that Italy had to force its role in the Libyan crisis in order to remain central in unraveling its solution.

Haftar’s dirty game

As soon as he returned to Benghazi from Paris, Haftar was interviewed by Asharq Al Aqsat. In the interview he stated that: he will run for president; the UN envoys designated so far are manipulated by the Islamic front (the new envoy Salamé has not been accused yet); this is Fayez Serraj’s last chance to hold true to his word (in another interview he told Serraj to go back to being an engineer); the Misurata militias will either bow or be destroyed; he is contrary to a federal system in Libya. In another public statement, Haftar even publicly praised Gheddafi’s son Seif al Islam, saying that he could play a political role in Libya’s future. This proves that the general is supported by former Gheddafians. After the statement, Seif al Islam immediately exchanged the favor by accusing Italy of having fascist and colonialist aims on the country.

The strong man in Tripoli (backed by Misurata’s militias) is the number two-man in the presidential council, Ahmed Maetig. Maetig didn’t appreciate the meeting between Serraj and Haftar and took advantage of Serraj’s absence to gratify economically Sirte’s militias. During operation Bunyan Marsous, these militias had fought the ISIS, while others had battled for control of the Tripoli international airport against the Zintan militias (allied with Haftar). This was a way to affirm Maetig’s independence and the armed support that makes him strong. Maetig was also disturbed by the fact that Serraj made an accord with Haftar without first consulting the presidential council.

Il capo del Consiglio Presidenziale libico Fayez Al-Serraj

The Paris accord In the light of these internal and foreign reactions, we can safely say that the Paris accord did not ease national reconciliation in Libya. In fact, it hindered it. The ten points of the Paris declaration, that were pompously undersigned by the two Libyan contenders and endorsed by a smiling Macron who sang the praises of the two courageous signatories was but a list of good intentions: the Libyan crisis can only be solved politically; the commitment to end hostilities; the commitment to recreate the conditions for a state of right in the country and to unify the institutions while guaranteeing the respect of human rights, of sovereignty and territorial integrity; a full application of the Skhirat accords; the Presidential Council and the Tobruk Parliament should play a role in the political debate; the bilateral meetings should continue to take place; the parties will strive to create conditions favorable for elections; an effort will be made to integrate the various armed groups into the national Libyan army (it is not yet clear whether we speak of Haftar’s Libyan National Army or of the militias that back Serraj). In addition to all of this, there is the commitment to fight terrorism (even though the term has different meanings for the two contenders) and to fight the phenomenon of illegal immigration (perhaps to soothe Italian irritation). Many words were spent, a lot of good intentions were expressed, but there is nothing that indicates an acceleration in the resolution to the Libyan crisis. Perhaps French president Macron didn’t really care about all of the above. Maybe he just wanted to play the self-proclaimed, prestigious, international broker and find his niche in the Libyan issue. And maybe he needed to gain credibility in the French military milieu after he ousted the head of the French armed forced, General Pierre de Villiers. The last consideration is a historical paradox: France, which under Sarkozy had forced the military ousting of Gheddafi and triggered the social chaos that today reigns supreme in Libya, is now playing the peacemaker in the north African country. Sometimes history has a very short memory.